We don’t make mistakes; we just have happy accidents.

-Bob Ross

What makes a great photograph? Henri Cartier-Bresson coined “the decisive moment” while Robert Capa believed if your pictures are not good enough, you’re not close enough and Don McCullin wanted people to feel something in his work. Robert Frank said photography must contain the humanity of the moment and William Klein spoke of individuality, even if clumsy, so long as it doesn’t look like somebody else’s work. Now more than ever the lines of photography become more and more blurred. With digital technology the scope of photography is almost limitless. Even my own ideas of what makes a good photograph has changed and evolved.

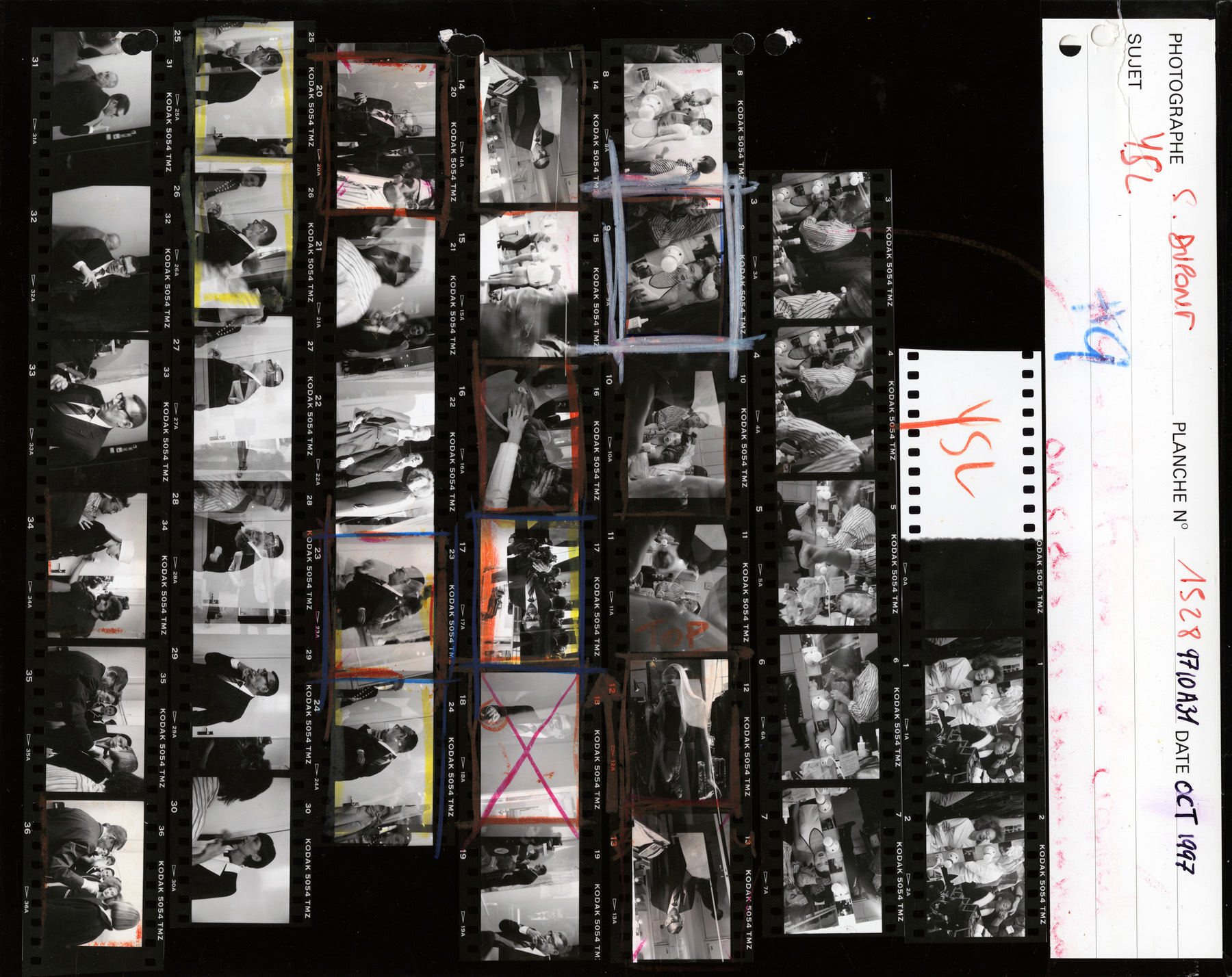

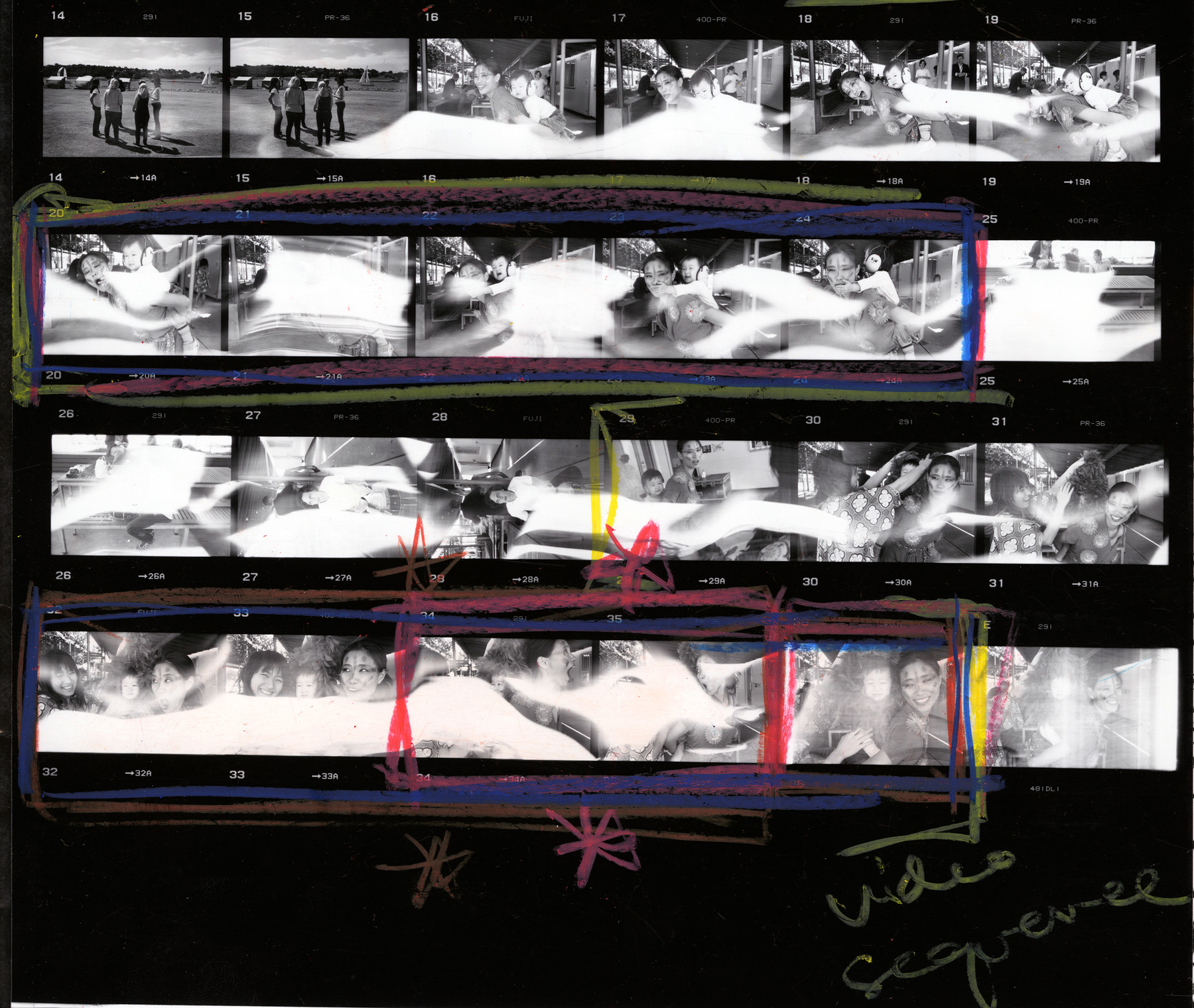

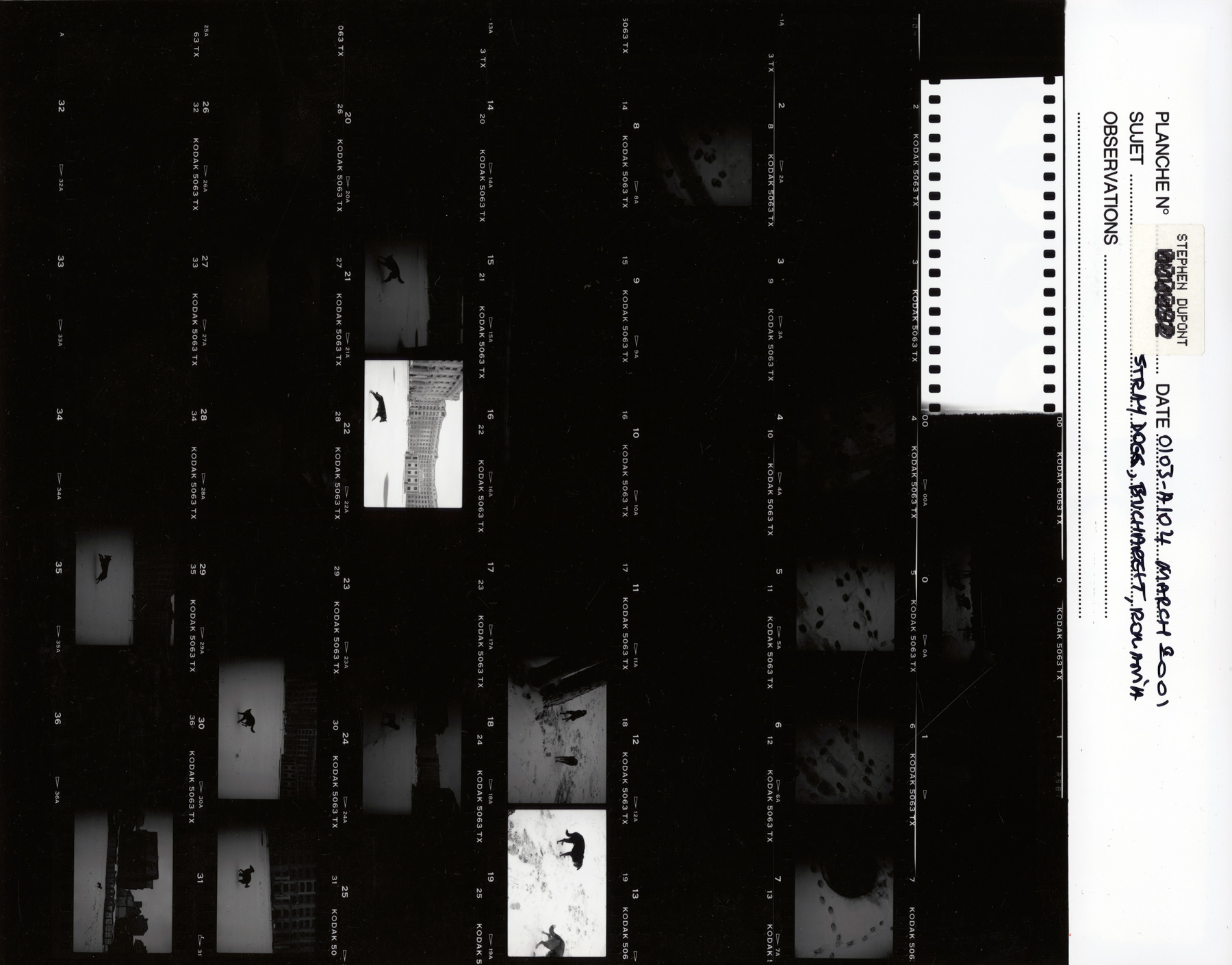

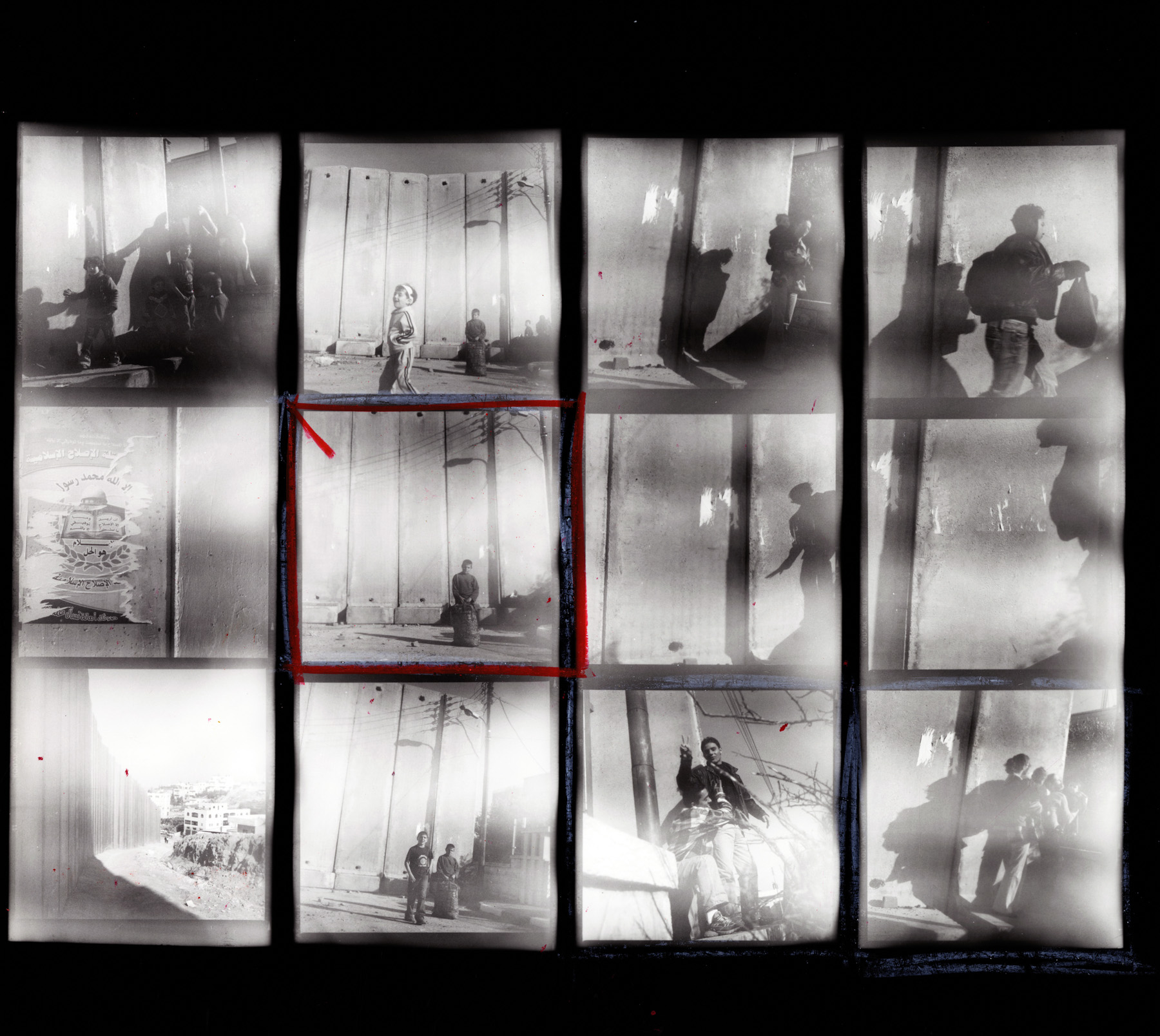

I’ve spent a lifetime editing my photographs and I have held onto everything. Contact sheets and negatives kept in their original state, nothing thrown away. China graph marks scar multiple editing sessions over the years by myself and others, immortalising the choices. Even my reject slides sit in boxes or plastic sleeves waiting to be looked at again some day, or not. Everything is meticulously archived.

Every photographer struggles with editing, I know I do. We might be too close to the story, allowing our feelings and experiences to take over our otherwise better judgment. Often two very similar photographs compete, which one is the best? Mood and timing might infect our decision-making. Outside influences can cloud our choice and process. The challenge is to disconnect one self from all of this; be the outsider looking in.

Gazing over my contact sheets from years past I’m often surprised by my original edits. Many gems overlooked, a visual diary of surprises and memories. My eye for photography is quite different from twenty years ago. I’m less constrained now and much more open-minded. What once may of seemed like a bad mistake can now be considered art. When editing I’m still searching for the most powerful photographs, the single iconic moments and those that thread a story together. I need to be moved and surprised before I put pencil to paper. Most of these choices are for magazines, newspapers or books. I have the final say and I want my best work to be seen.

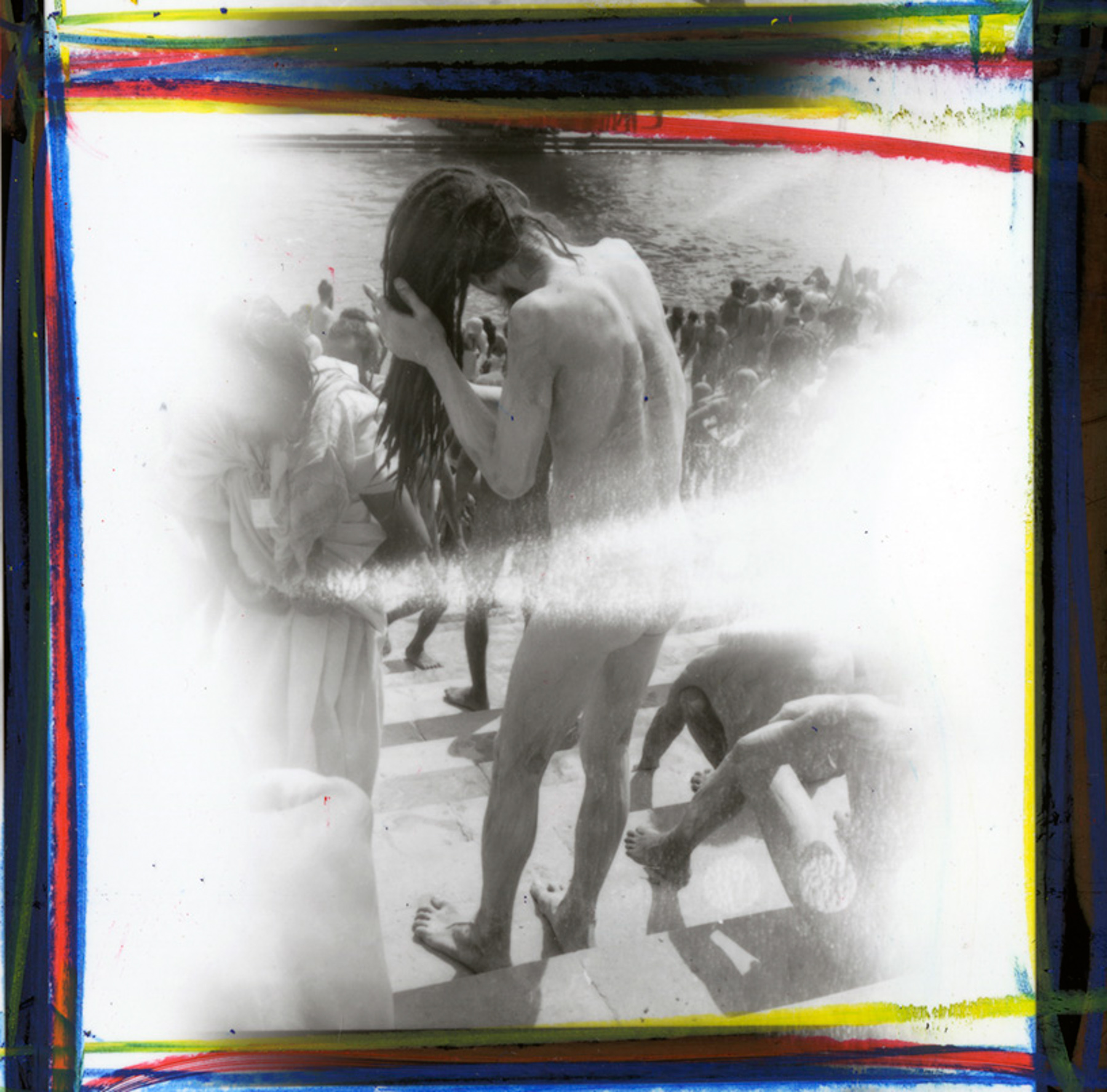

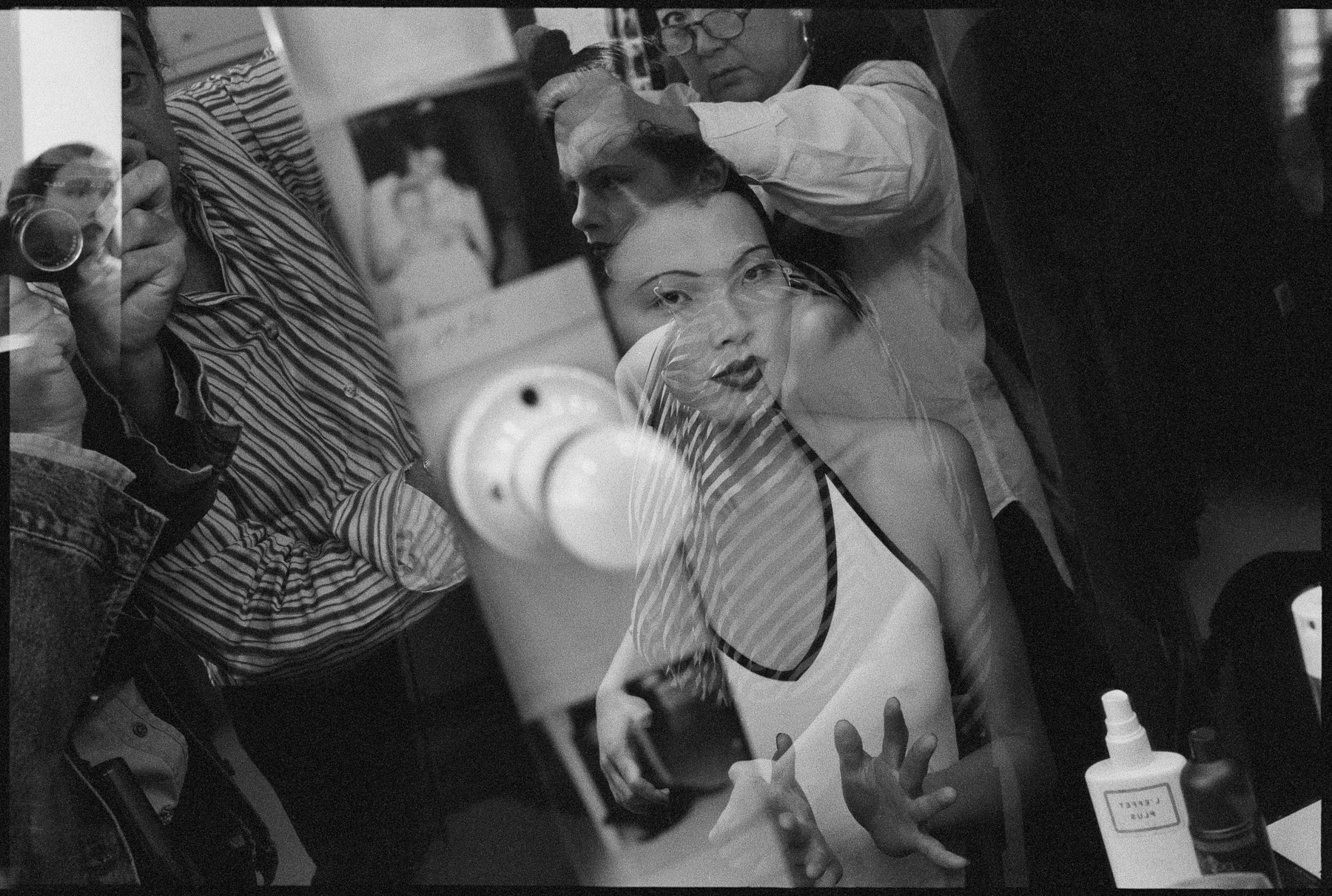

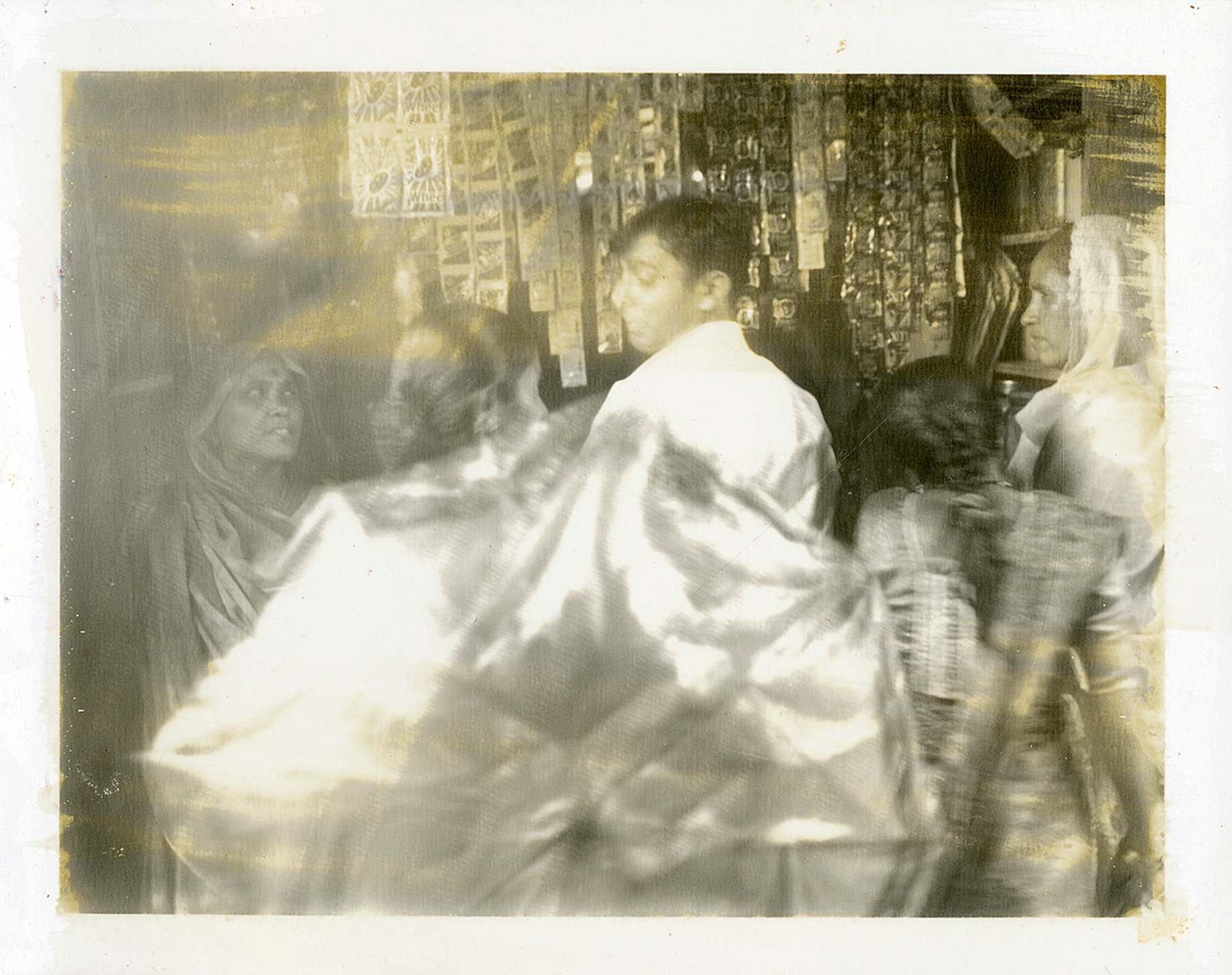

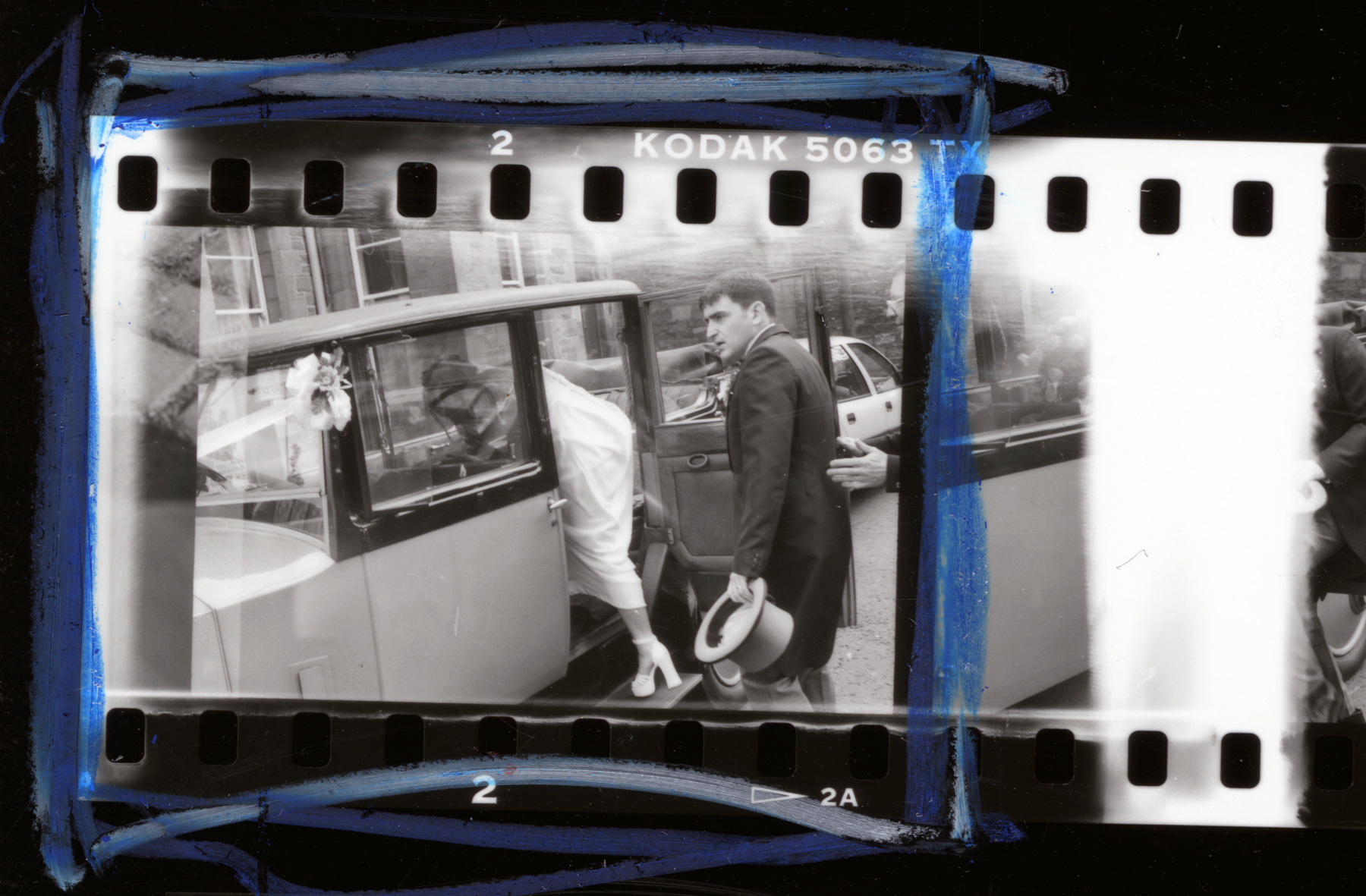

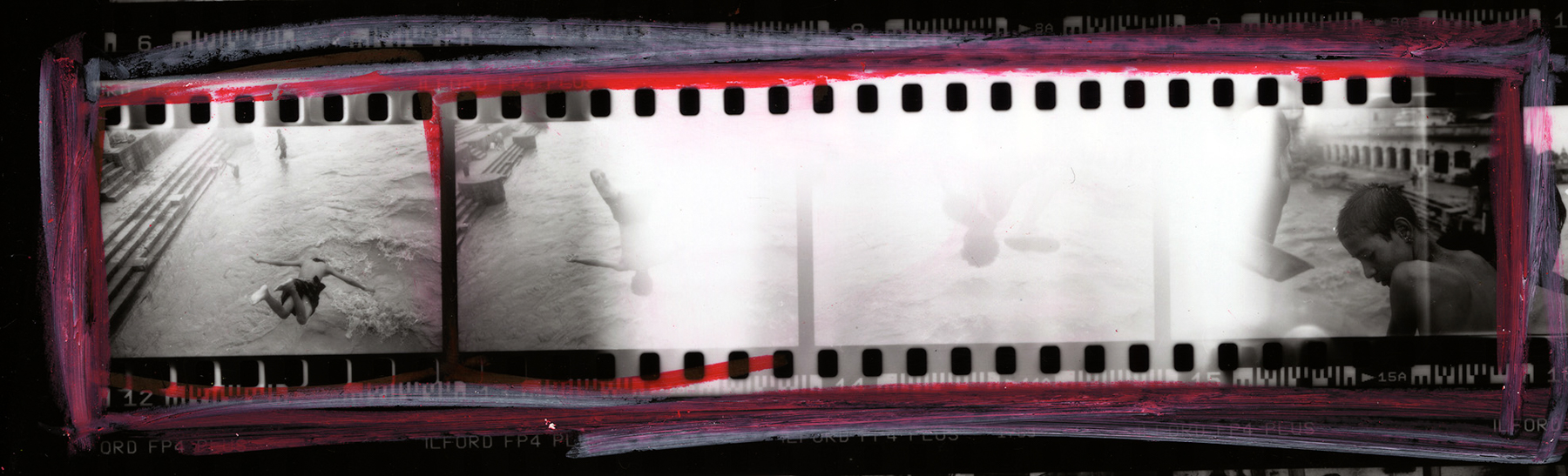

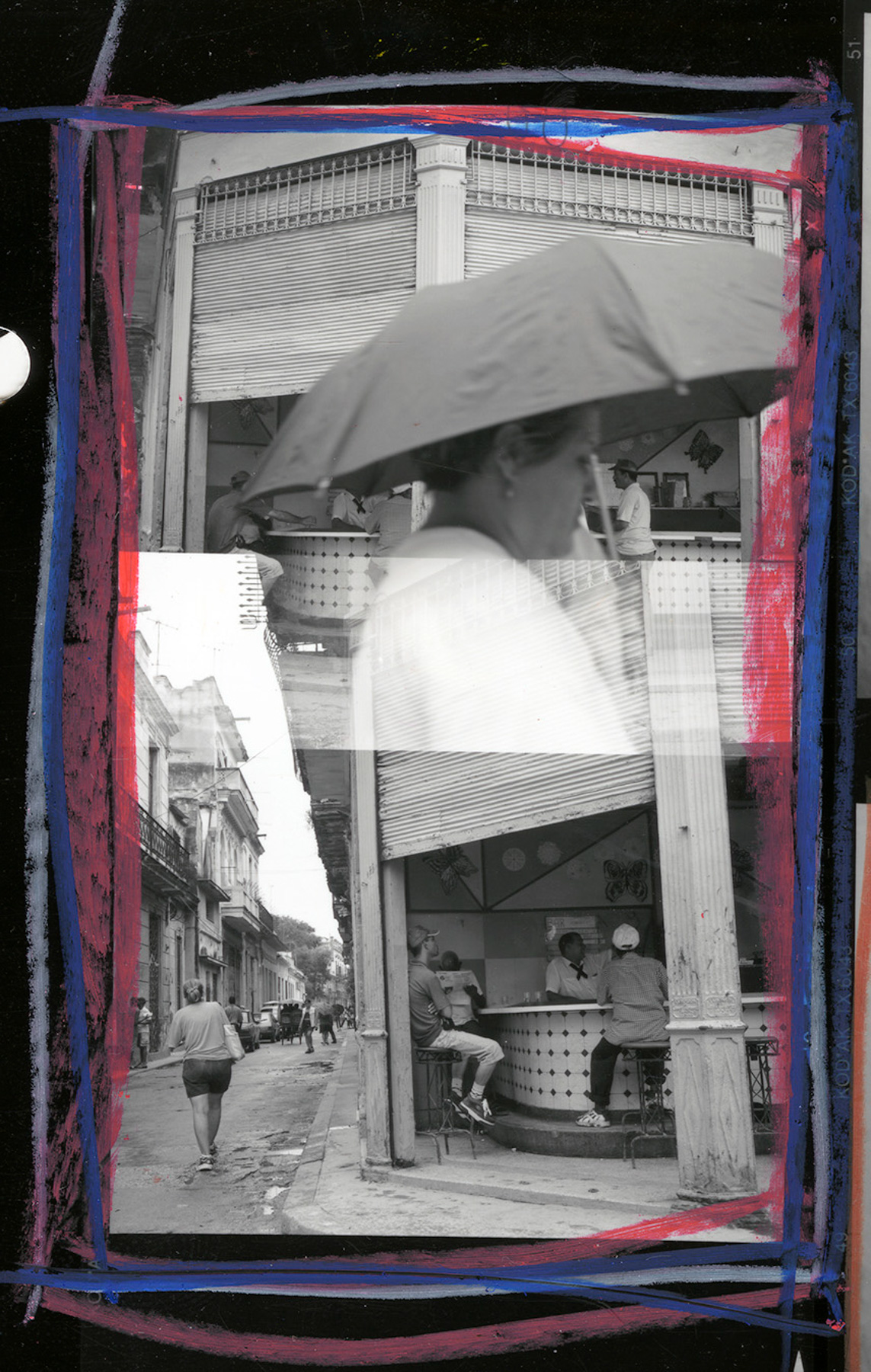

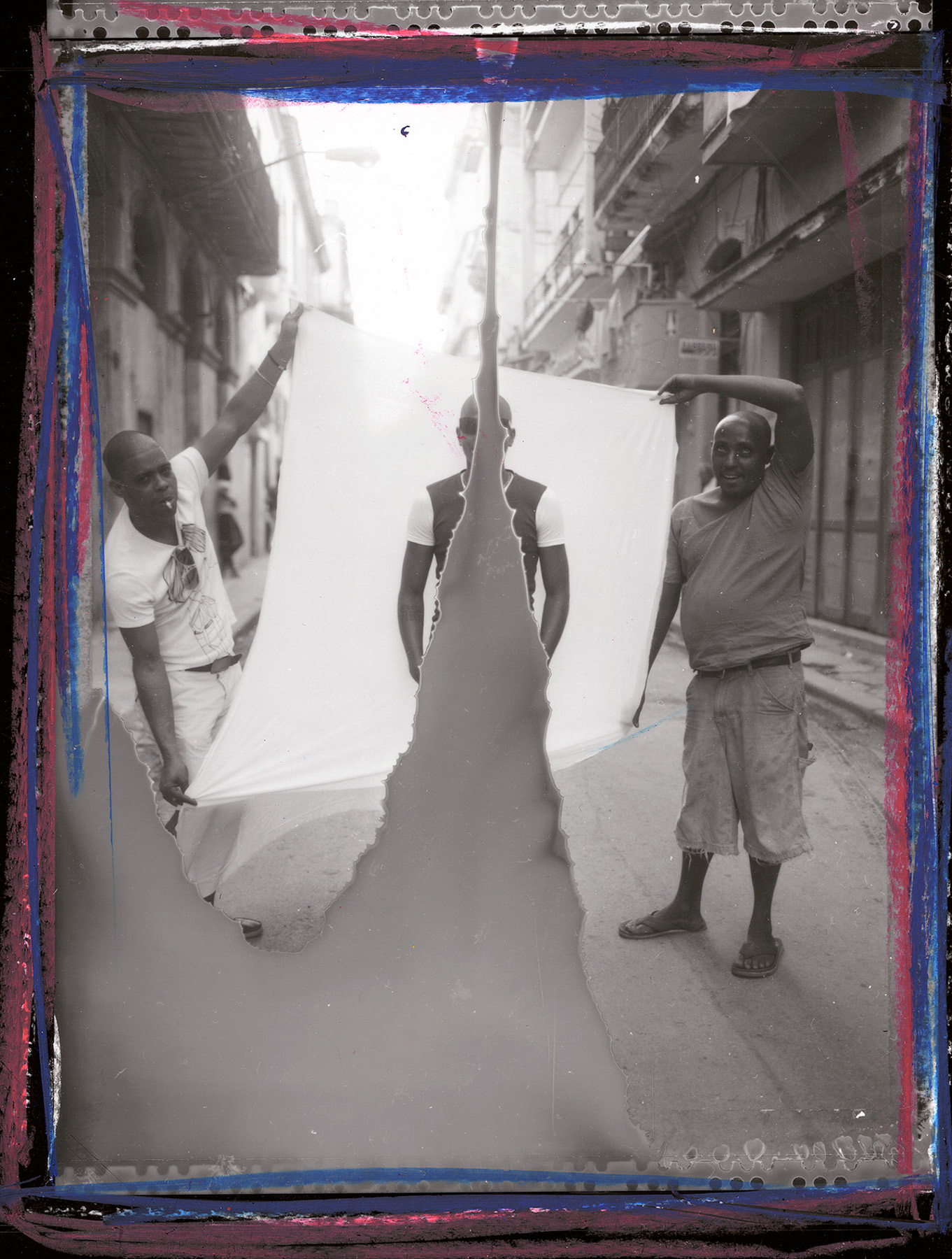

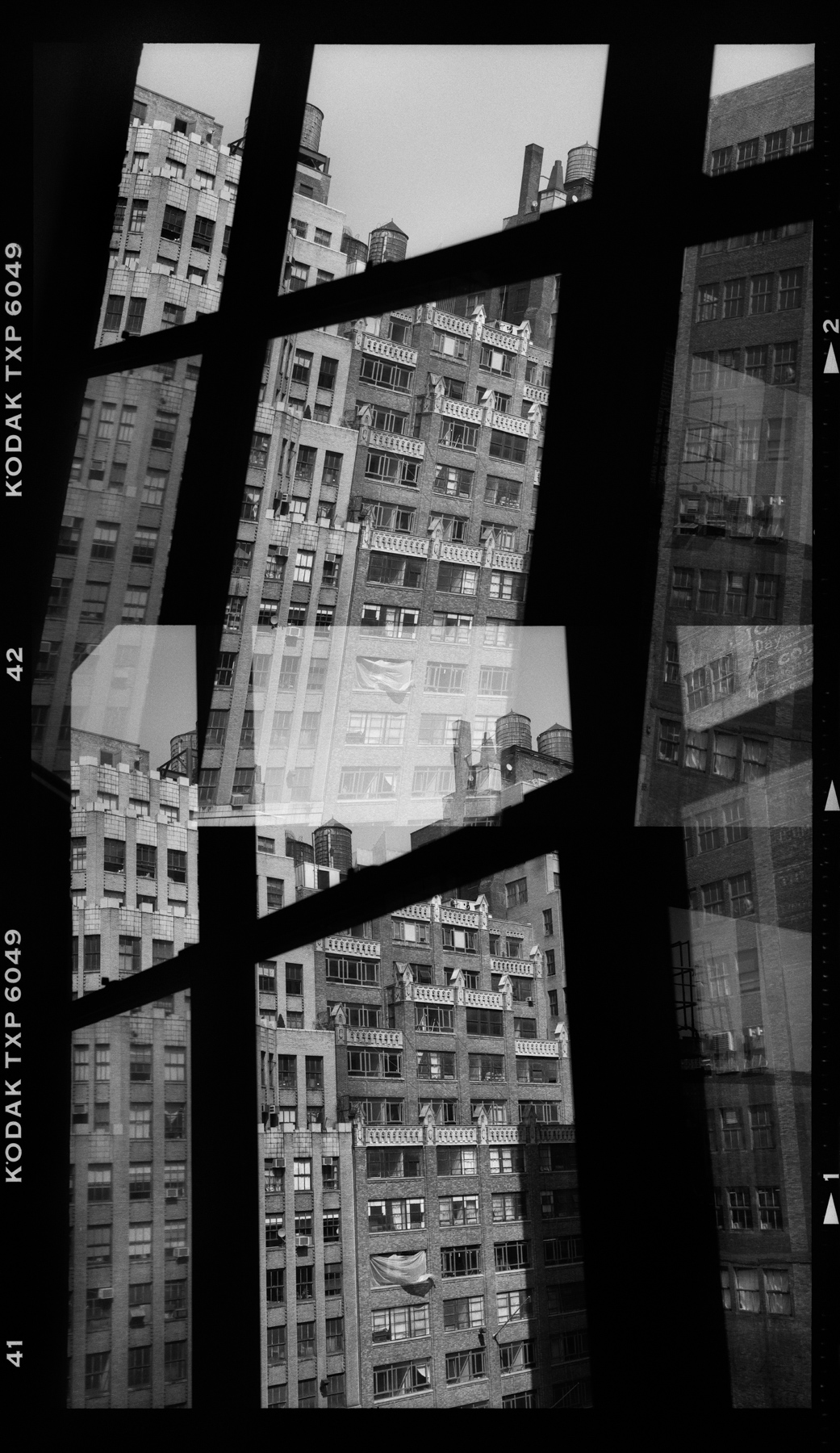

This book, however, is not about my best work. It features only the work that I originally overlooked. They are the mishaps; mistakes and general fuck-ups along the way, photographs that would have never seen the light of day. Now they stare back at me with a vengeance, reminding me of the times I opened up the back of my camera exposing the negative to sunlight, forgetting I still had an unwound roll of film inside. Or how I over-processed films in the dark room, damaging the negative’s emulsion, reticulation and worse. Double exposures, flash sync problems and out-of-date film stock.

Maybe I call this the destruction cycle of film?

Last trip to Israel I left through Tel Aviv Airport. Israeli customs x-rayed my films over ten times in three different machines. I patiently watched them literally cook them. Israeli intelligence fried my films on purpose. Back home when I saw the processed films I was devastated. But on second glance I could see a different kind of aesthetic, a different meaning to them. They spoke to me of political censorship. They were Art.

It’s the imperfections in photographs that makes them unique; beautiful; makes them great. Perfection is boring. I think it was Salvador Dali who once said, have no fear of perfection because you’ll never reach it.

Fucked Up Fotos takes my philosophy of imperfections to a whole other level. There is very little of me in these photographs. In fact, the images were not exactly made by me at all. Of course I created them, but who really made them what they are? Science? Nature? My own negligence? Outside interferences? These photographs, once dismissed as poor rejects, are sometimes extraordinary, magical and poetic. They’re destructive and layered moments; complex and mysterious, like a painting they invite us to look much deeper, revealing interwoven fragments of time and space. In the end they offer new meaning to the art of photography itself, like fractured puzzle pieces from a waking dream.