Fractured Dreams & Indefinite Scars explores the ways in which immigration laws and processes impact family narratives and histories.

This photographic project revolves around the personal experiences of five families, those of which have either been deported or threatened with deportation from Queensland. For many of those who are sent back to their birthplace, with little to no support system, the environments are unsafe or completely alien. The human experience behind the social and legal implications of deportation and the effects of being temporary and the invisibility of these lived experiences are important for us to reflect upon and be challenged by. Over the last decade the composition of those who are being deported has changed and is constantly shifting, from irregular maritime arrivals through to the current cohort of refugees on temporary protection visas and permanent residents who have lived in Australia the majority of their lives.

Fractured Dreams & Indefinite Scars aims to inspire an awareness, instigate conversations and encourage deeper understanding around how forced migration is experienced by not only the individual, but also their families and the community that surrounds them.

Achuthan

When Sri Lanka gained independence from Britain in 1948, power fell to the Sinhalese majority. The minority Tamils faced employment discrimination, restrictions on education and violent attacks. There have been massacres of Tamil civilians in what some refer to as nothing less than genocide. Achuthan comes from a long lineage of freedom fighters and started fighting for freedom when he was 13 years old.

After 26 years, the Sri Lankan Civil War officially ended in 2009. Up to one million people were left displaced. In the aftermath of the war, Achuthan decided to board an asylum seeker boat in 2013 with little understanding of where he was going and what the journey entailed. He spent 22 days inside a boat, eating only once a day, setting out to find freedom. Achuthan arrived at the Cocos Islands, only to be transferred to Christmas Island for 11 months, then Nauru for seven years before being medically evacuated to Brisbane.

Achuthan was detained in a Brisbane detention centre for three months and then moved into community detention where he was not allowed to work or study. He is currently on a bridging visa and in a precarious state of limbo, uncertain what the Australian Government will decide. The Australian and Sri Lankan governments work closely together to stop people coming to Australia by boat. Human rights advocates are fearful of the consequences for those who are being sent back, as abductions, imprisonment and surveillance of minority groups is not uncommon. Achuthan left Sri Lanka when he was 18 years old. He is now 25 years old and still seeking status as a refugee. Achuthan is a carpenter. His dream is to move to a regional area and build his own house and to support his community in Sri Lanka.

Baaraan

Over the last three decades, many contributing factors have caused mass migration of Iranians to other countries including political instability, prolonged violence, conflict and severe human rights abuses, particularly towards women in both their private and public lives.

Asylum seekers have attempted to reach Australia on boats from Indonesia, often paying large sums of money to people smugglers. Hundreds have died making the dangerous journey. There are a significant number of Iranian asylum seekers living in Australian communities, many of which are waiting decisions on their claims for asylum. According to the UNHCR, only one percent of refugees worldwide are resettled in their lifetime. In community detention asylum seekers have the opportunity to move around in the community, engage in activities and social events, and experience some semblance of normality.

The experience of being held in detention centres has negative and long-lasting impacts on the mental health and well-being of many of the people seeking asylum in Australia.

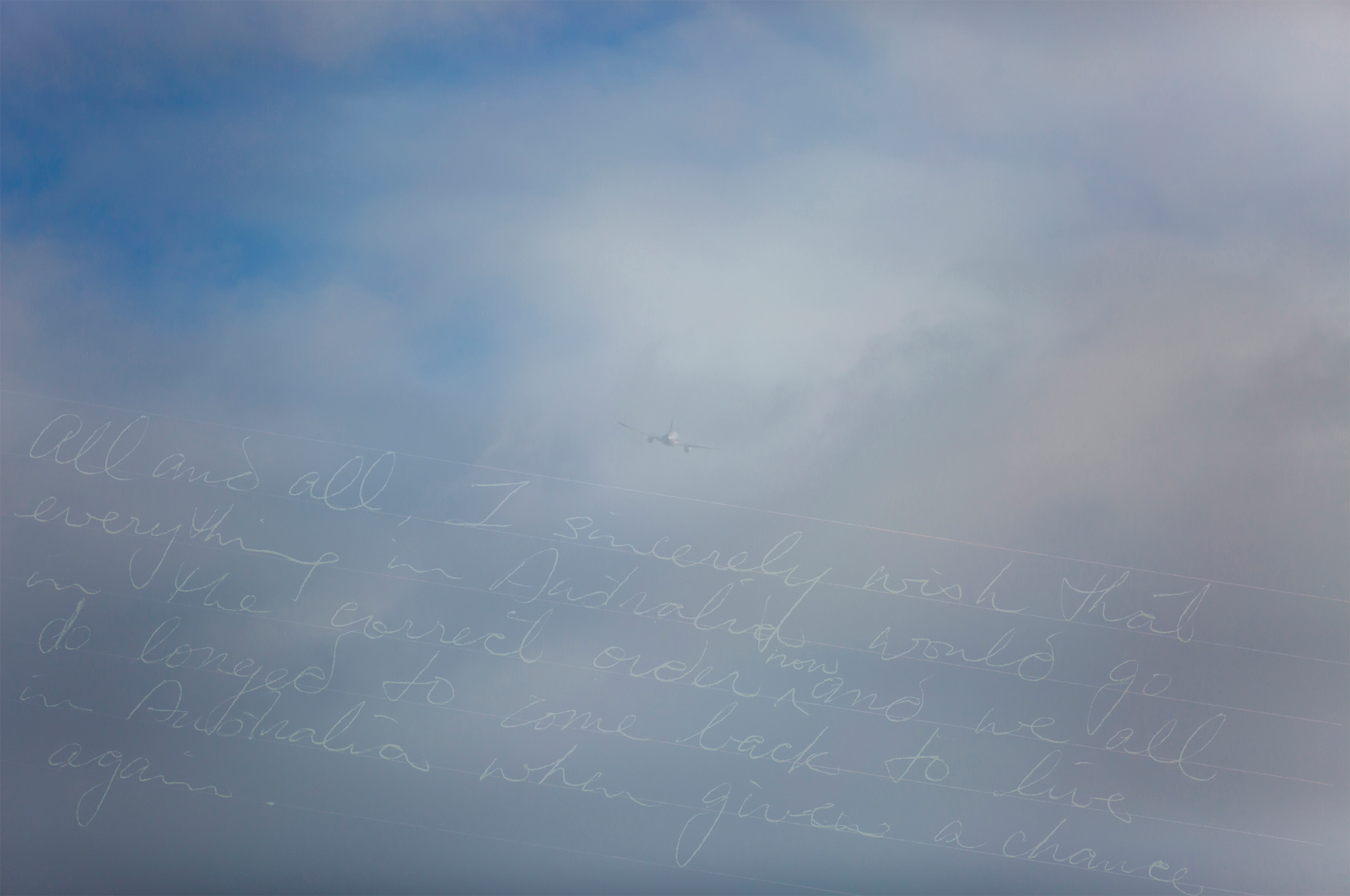

Jenny

1986 marked the year three generations of my mother’s family were deported from the Sunshine Coast. My mother, Jenny, was pregnant with me at the time. Since becoming a mother myself, I have reflected on the ways in which trauma can be intergenerational, how it can reside in your DNA and be passed down indefinitely. My mother’s family chose to flee from Hong Kong to Australia, with the understanding that in 1997 Hong Kong would be handed back over to China. They feared for their futures and safety living under the rule of the Chinese government. There were boxes and boxes of belongings that were left at my mother’s house and there are items that still remain unboxed and buried amongst her belongings, objects that are unbearable for her to part ways with.

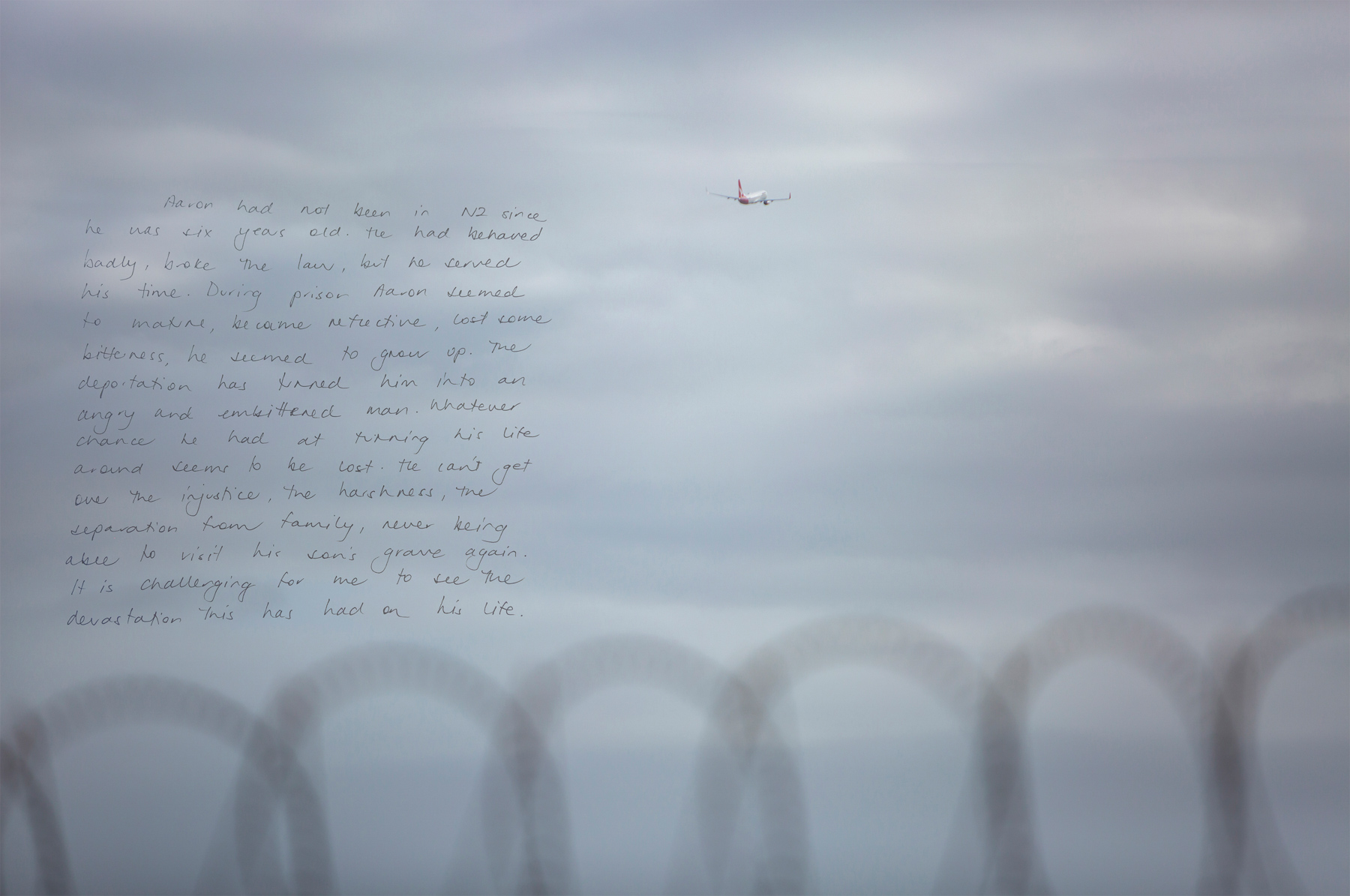

Kylie and Aaron

In 2014, the Australian Government tightened the visa character test, paving the way for almost 5,000 deportations of non-citizens with criminal records, the majority of which were from New Zealand. Under the laws, long-term residents who have served 12 months or more in prison, or believed to pose a threat to the country, could be deported.

In his research, Professor Peter Billings (Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Queensland) explores Australia’s policies that have led to the increased detainment and removal of people who are long-term permanent residents, or ‘virtual nationals’ – people who have been living here for decades, since early childhood in many cases. This group of people labelled as criminal deportees includes those who have committed heinous crimes, such as murder or serious sexual offences, but also those with more minor criminal histories – such as people who have committed minor traffic offences or those with convictions for drug related offences.