Liss Fenwick’s Back Out was recently shown at Lennox St Gallery, a longstanding art space in a leafier corner of Richmond. The show comprised seven close-cropped images of scenes around the artist’s home town of Humpty Doo – a small rural and commuter community fifty kilometers south of Darwin.

Per Fenwick’s artist statement, these unstaged – though artificially lit and highly saturated – images comprise a counterpoint to romantic depictions of the Australian landscape. The exhibition forms part of Fenwick’s critical engagement with the status of (predominantly white) residents in the rural community the artist grew up in and continues to identify with. (The artist is a white PhD candidate at RMIT, and splits their time between Victoria and the Northern Territory).

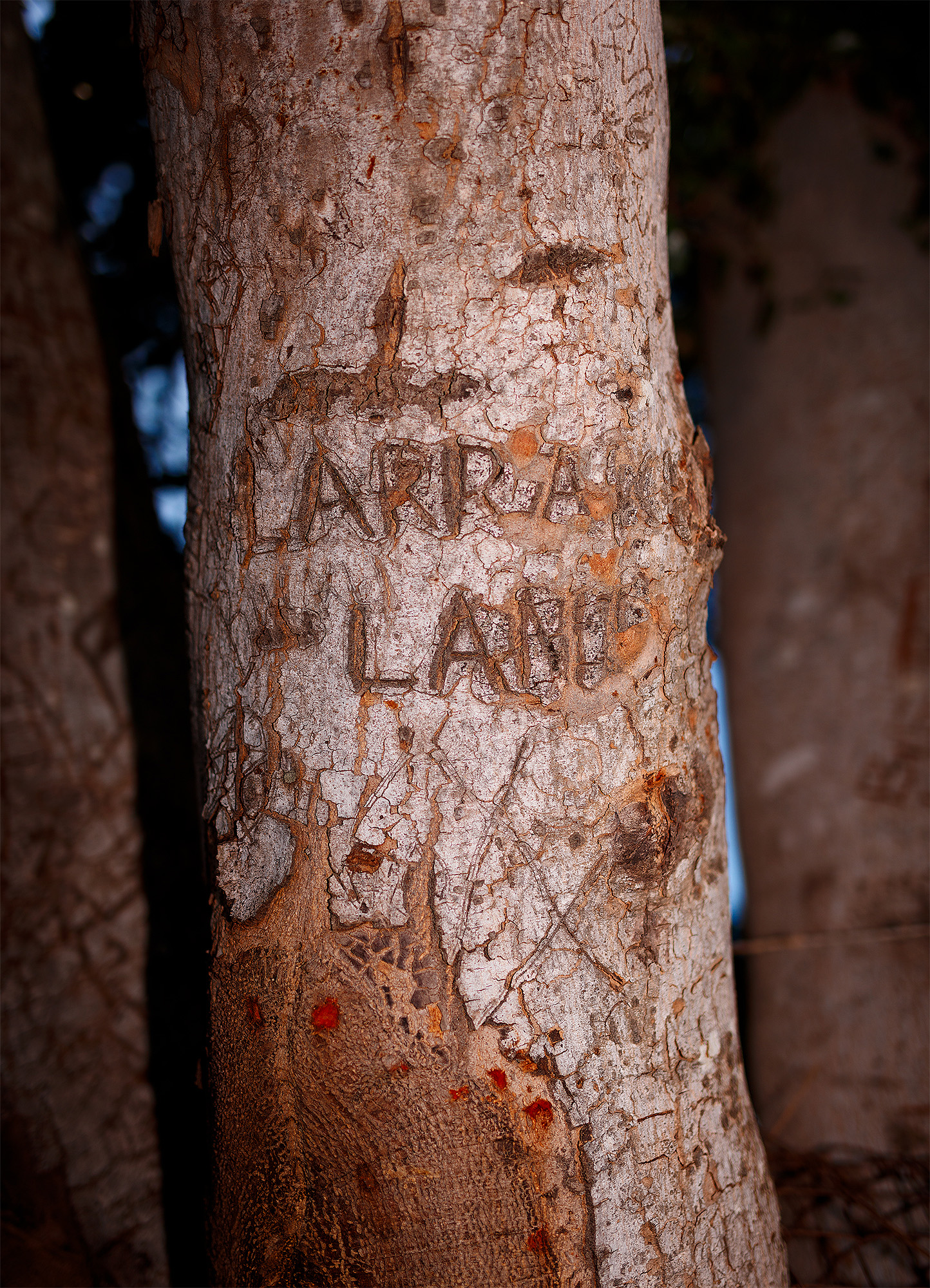

The exhibition consists of imagery formed around Fenwick’s home town of Humpty Doo, NT. The photographs include a meat ant entering the fleshy puncture in a paw paw left by a bird raiding a roadside fruit stand, the shattered and melted tail light of one of the many burnt out cars surrounding Humpty Doo and the artist’s brother dressed for a fishing trip, framed from the shoulders up. His face is wholly obscured by a skull buff and other masculine accoutrements familiar from military videogame box art. Sunglasses, hat, a smear of reflected light across the former; no visible face to speak of. Other pictures include the words “Larrakia land” carved into a tree trunk and a tattered Australian flag hanging from a fence.

It’s worth considering here the invitations that staged and unstaged photography extends to its viewers. Fenwick’s practice spans both, and there’s a tension in how these operate that may be crucial to the work.

A danger in affecting the style of documentary photography, as Fenwick does in Back Out’s collection of unstaged frames, is that documentary purports to show the viewer “what is”. And when presented with facts, the audience is invited to receive, rather than create, meaning.

As anyone with a passing familiarity with the news will know, this often serves to reinforce rather than expand a pre-existing understanding of the subject. Not necessarily by some propagandist sleight of hand, but because documentary presents such a tiny subset of reality that it is wholly reliant on context. Presented with the peg of what is, we search quickly for a contextual hole that fits.

Given that Back Out largely comprises scenes referencing a kind of white rural ugliness – the tattered flag, the aggressively clothed man, the counterpoint of Larakia Land carved into a tree trunk – and Fenwick’s own wordplay of “outback” into a description and injunction of defeat – I would suggest that the readiest contextual hole for this show is not romantic landscape painting, but the generally agreed-upon idea that white rural settlement is fucked.

And I mean, yeah, fair enough, that sort of critical engagement is not unjustified. But also fairly well trodden ground (witness such readily-identifiable footprints as Wake in Fright, or Juan Davila’s obscene(ly ocker) paintings). Moreover, when viewed in the aforementioned “leafier” Melbourne corner, it’s also an airy and weightless thing. To view a critique of the failures and transgressions of settlement from within a space where the project is already complete and irreversibly entrenched is something abstract and consequence free.

Which of the attendees of a show indexing “places that don’t matter” stands to lose anything from the collapse it portends? Fenwick’s image of the carved tree trunk denoting Larrakia Land was taken on a part of the Cox Peninsula barred from further settler development in 2016. Which of the (multiple) buyers of the show’s hero image of a tattered Australian flag hanging from a fence stand return any of their Melbourne properties to their traditional owners? This sort of thing, in this sort of place – pet nat wines, statement earrings, architecture practices, etc – can be an exercise in self congratulatory class-blind bumpats and little else.

And yet. Refer back to the question above, about what staged and unstaged photography asks of the viewer.

Back Out is an exhibition that was awarded to Fenwick on the strength of their showing at 2021’s NotFair Art Fair, where the artist showed a series of staged photographs called Meat Tray. That work comprised a series of artificially lit, close-up images of meat ants consuming buffalo flesh, which the artist had laid out on silver platters at their parent’s Humpty Doo property.

An extended read of the colonial associations of silverware and the artist statement accompanying Meat Tray referencing the nihilism of depressed rural communities is beyond the scope of this essay. But I think it’s generally understood that any image constructed for a particular purpose suggests a symbolic reading.

The audience is invited to take the materials offered by the artist (eg: tray, ants, light, words, etc) and make art through the conscious and deliberate process of engaging with how they might fit together. The resultant work hovers, invisible, between the active viewer and the cues that the artist has provided.

Given the thematic and formal overlap here (the close ups, ants, lighting, location), it’s fruitful to engage with this series the same way. After all, Fenwick’s own statement appends an intriguing coda to their critical engagement with the territory. “My broader practice,” they write, “involves efforts to befriend, value, and make meaning around landscape elements, such as meat ants, termites and trees, as a possibly futile yet tender counterbalance to a fractured relationship with land.”

Consider the meat ant’s roadside transgression into the punctured paw paw, and how permeable boundaries are presented throughout the series. Shattered car (per Ballard, a kind of stand-in body), the multiple protective layers on Fenwick’s brother suggesting something vulnerable inside; the bark around the words “Larrakia Land” encroaching slowly on the words. What does it mean for the largest image in this show to depict a tree growing into the barbed wire that has been nailed to it?

Honestly, I don’t know. The perspectivist underpinnings of Fenwick’s work are too dense for me to grok assuredly, and I suppose that doing the work oneself is part of the symbolic art bargain. But I have ideas.

It’s convenient, perhaps, that Humpty Doo is in a hot part of the world, because I’m not sure what metaphor I’d reach for to engage with a similar show about a more temperate place. But still: there’s an experience of heat and humidity in the top end of Australia that is impossible to experience in the abstract, because the discomforts it entails anchor the body to its environment. The experience of sweating, of rationing one’s attention through the course of a hot day, and of respite when it’s available, remind you over and over of where you are. That whatever the specifics of your presence are – good or bad – that you are a part of that place and complicit in its use.

The softer elements of Fenwick’s work, the gentle engagement with boundaries and transformations in the actions of insects and trees, do speak to that, I think. They form a kind of presence and engagement in that landscape; a sense of something approaching surrender. Of the land operating in turn on its inhabitants.

As Fenwick writes, perhaps there’s a futility to that tender counterpoint. How does a relationship with the land – on the part of a white resident, or the white art viewer in affluent Melbourne – sit alongside an acknowledgement of the repercussions of settlement?

I don’t know.

Another of the close-ups in Back Out is of flying termites swarming on a discarded hat during their nuptial flight. A rare, delicate and privileged sight. A flat-out experience of beauty.

A central aspect of Fenwick’s work seems to be a critical engagement with their own membership of the white Territorian population, and the complexities of that position alongside their position in the art world. Perhaps these gentler cues serve to invite the viewer into the scenes Fenwick documents, and complicate their relationship to land beyond the easy act of casting critical judgment. What movement there is beyond that – perhaps an acceptance of some loss of assumed primacy; a surrender of sorts – hovers between the viewer and image.