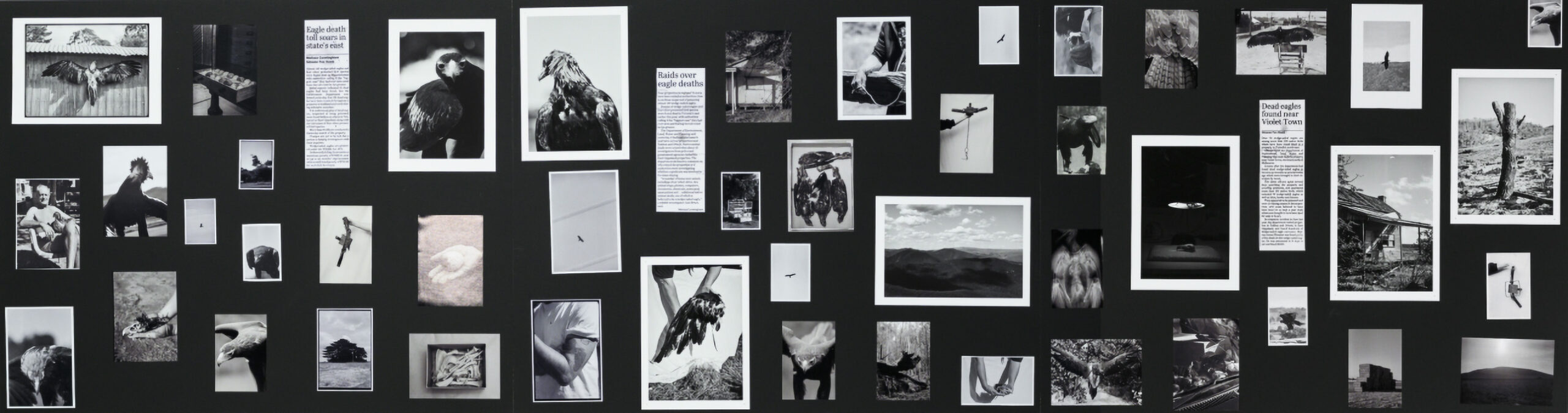

Exhibition pictures by Annika Kafcaloudis

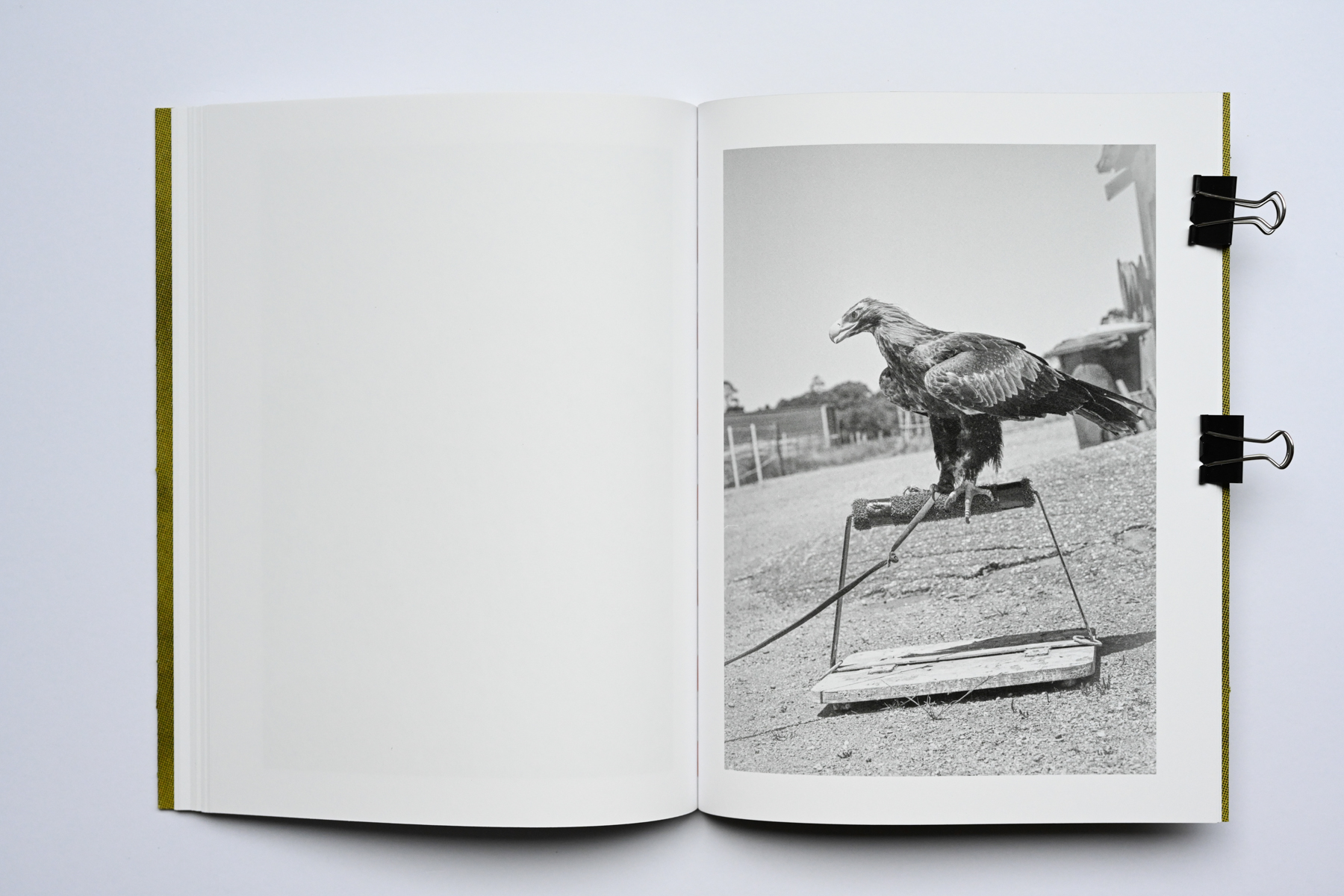

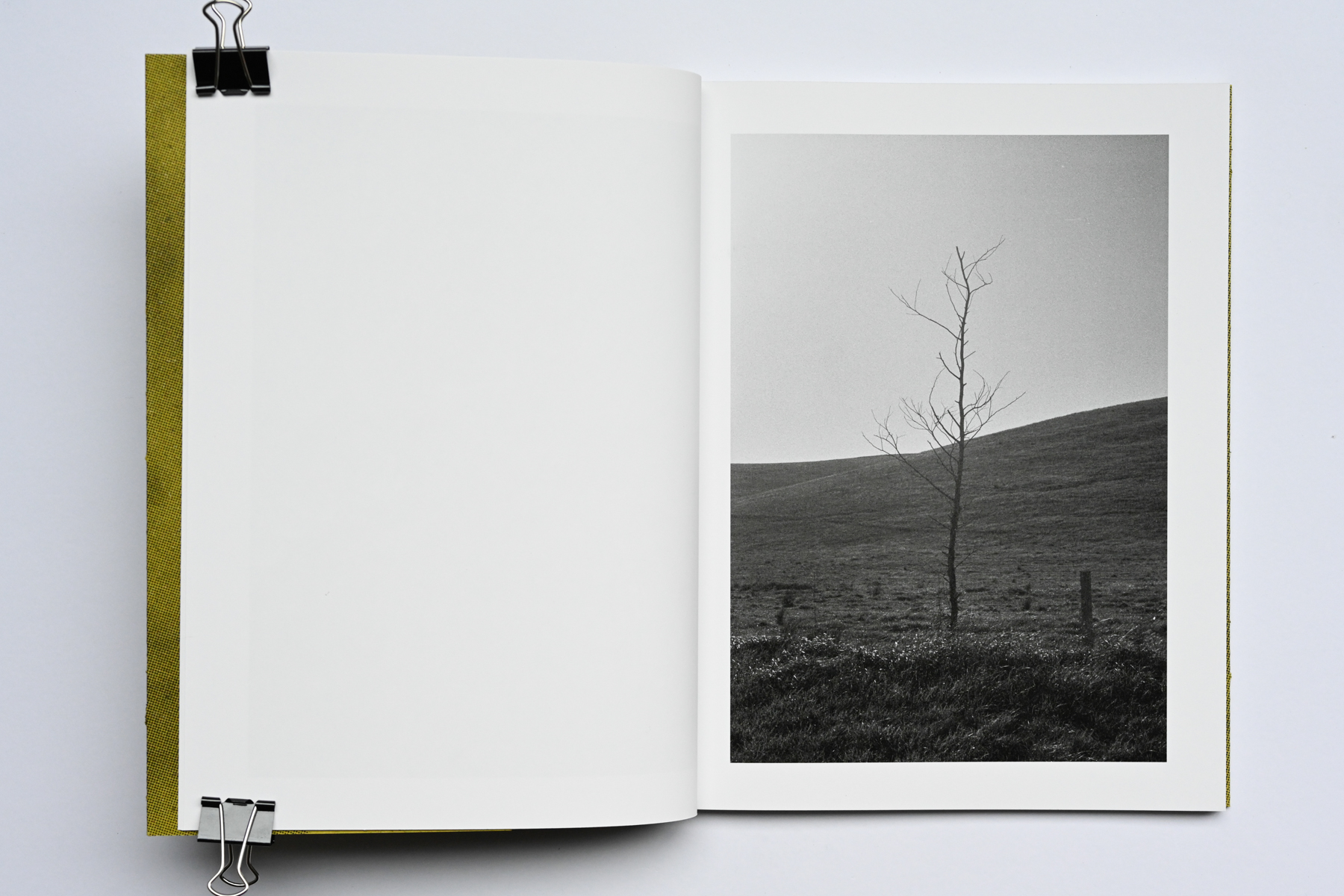

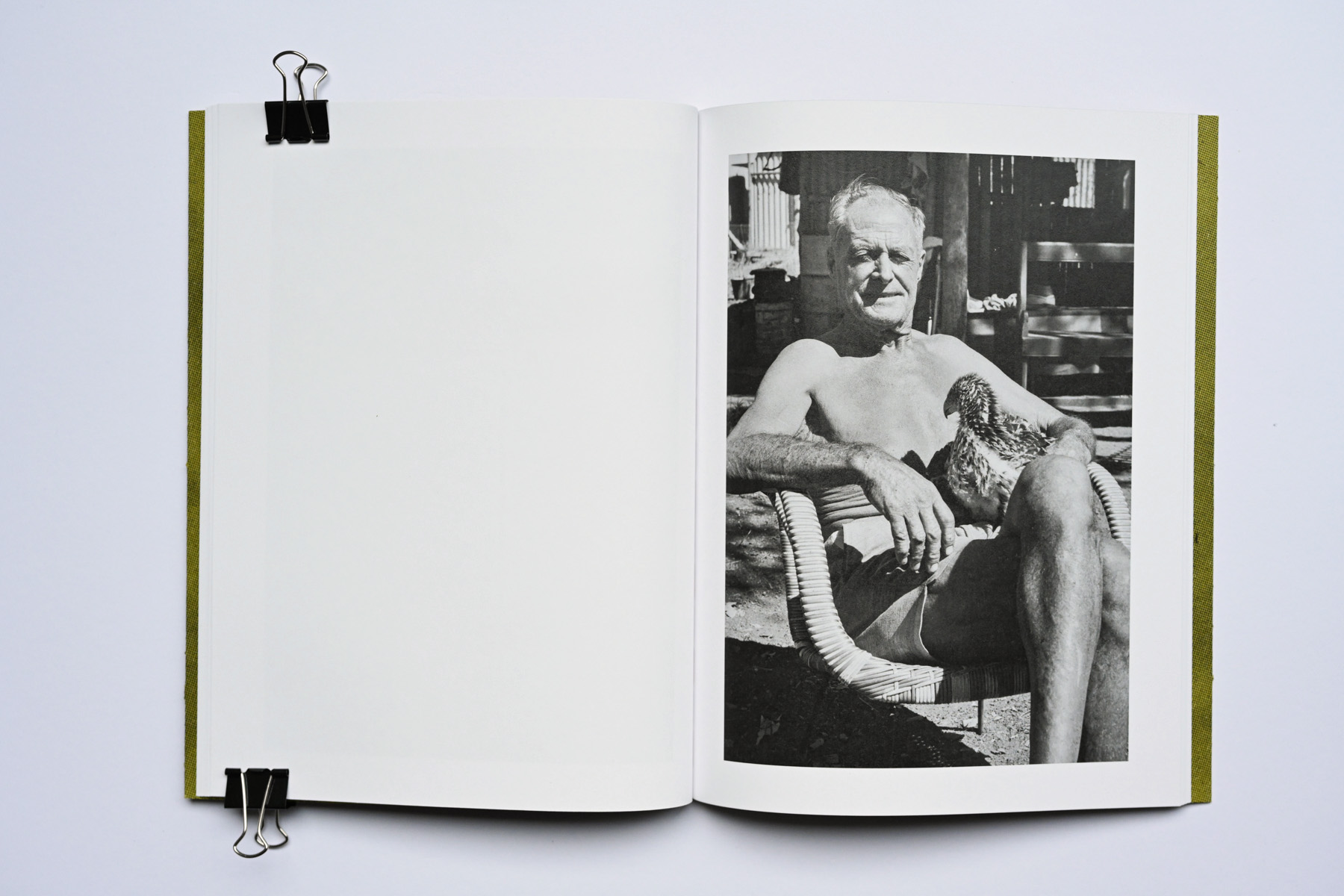

All other photographs by Matt Dunne

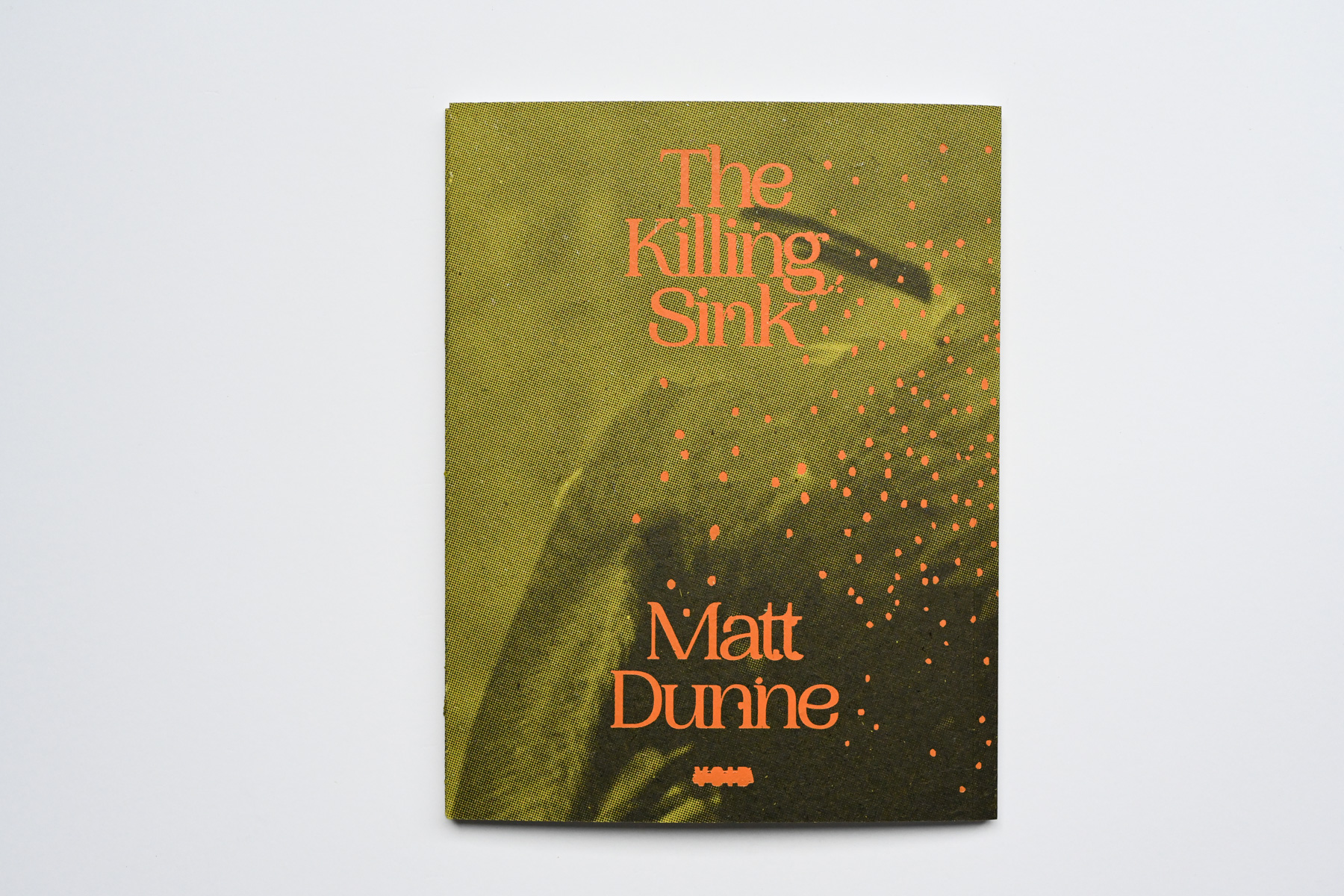

Tom Goldner recently caught up with artist and publisher Matt Dunne to chat about his most recent project, The Killing Sink.

TG: To me, you seem like somebody who wears lots of different hats in life, especially when it comes to your creative endeavours. When making ‘The Killing Sink’ do you identify your role first as an artist, conservationist, documentarian or something completely different?

MD: Artist first, definitely.

TG: That grey area, or space which exists between the photographs is something I think about a lot. I feel you balanced that very consciously between both in the book and the exhibition.

TG: Tell me something about one of the photographs in the series which you haven’t had the chance to talk about before.

TG: At the exhibition you spoke a little about your interaction with people in the making of the work, particularly of the communities in Gippsland where some of the crimes against wedged-tailed eagles took place. Can you share with me a story or two that impacted you one way or another?

TG: Tell me a little about how you came to the sequencing in the book. Was that an ongoing dialogue with the folk at Void or did you hand the material over and trust them in the process?

TG: Interesting. I love the idea of zooming in, zooming out. I’ve found living semi-rurally that I’ve become more aware of some of these ‘slow emergencies’. The wild onions are always an impactful one for me, you don’t notice them for 11 months of the year and come early spring the country is overflowing in these delicate white flowers and the whole countryside is filled with the smell. They are very pretty but it is causing all sorts of problems for the native flora and fauna.

As much as I didn’t want my project to be didactic I understand the approach to conservation at times has to be. I feel I understand the need to cull because the damage occurring from the horses is real and the flow on effect causes death. As you said, killing to allow for living. On the other hand these horses are beautiful animals, it shouldn’t be an easy thing to kill animals which are only here because we enabled it. It’s an uncomfortable thing to position oneself as part of these systems but I came to feel it provided a more balanced perspective.

It might be a somewhat naive question considering all the grey areas we have talked about during our chat but I’m wondering if you feel hopeful about the future?

You can follow Matt Dunne at @matt.dunne and Tom Goldner at @tomgoldnerphoto

The Killing Sink is available for purchase here.