Could you tell us a bit about when you realised you were a photographer and how this process developed for you? What did friends and family think when you told them this is what you wanted to do?

I started taking pictures in 1976 when I lived in a group household where there was already a darkroom. Ponch Hawkes lived with us and introduced me to photography and she said: “If you ever want to use my camera let me know.” She showed me how to process film and how to make a proof sheet and prints. So, I was kind of like “Whoa” – an immediate discovery, “I love this magic!” At this time, we were living and hanging around with people from many diverse subcultures like Circus Oz, the Pram Factory theatre, the rock n’ roll scene, etc. I was also working as a driver for Crawford’s TV production company in Abbotsford, Melbourne. Through all these connections I started to make photojournalistic work and quickly got paid for my photography.

A big leap in my career happened in 1978 when I visited Mermaid Beach for Christmas with my then partner Bob Daly, where I took many B&W images, printed them and then began to hand colour them. The series of 30 images, Christmas holiday with Bob’s family, was exhibited in 1979 at the George Paton Gallery. The National Gallery of Victoria and the National Gallery of Australia bought complete sets of the series in 1979/80. In 1980 I exhibited When a Girl Marries, a series of 32 images at the Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, which was also purchased by the National Gallery of Australia.

As my career started to develop my friends were always supportive and this was very important to me. My parents were not against my career path but initially worried that it was not secure.

How did you end up in Eden and what has it been like living there and documenting the community for so long?

My daughter Jo had been living in Bermagui for more than 10 years, and in 1992 Maddy, my first grandchild, was born. Every few months my grandmother nerves would tingle, and I had to go visit. My partner Bob and I were living in St. Kilda and decided to sell our house. We were both turning 50 and both artists with irregular incomes. We didn’t want and wouldn’t get a mortgage, so we went looking further afield. We went to Nowra and hired a car and started coming down the coast but most houses and towns were too expensive, too artsy, too ‘ye olde oppe shoppe’.

And then we came to Eden – a working class town! There were other factors involved with our move, but in the end, it was very beautiful, and we could afford it. Once again, I entered the community through photography. I started moseying around the town with my camera and slowly got involved with the community.

When I moved to Eden in 1996, I felt like I was over documentary. When you go to a new place, new things happen, and in relation to my work, I wondered what that would mean. It wasn’t long before I realised that the city and regional towns are parallel universes, but most people are unaware of this unless they have experienced both living situations. Soon, things happened that were documentary focused. I was commissioned by the Department of Planning and Environment to document people and place in B&W and colour for a sustainable future project in Eden, and it was an in-depth introduction to the larger community of Eden.

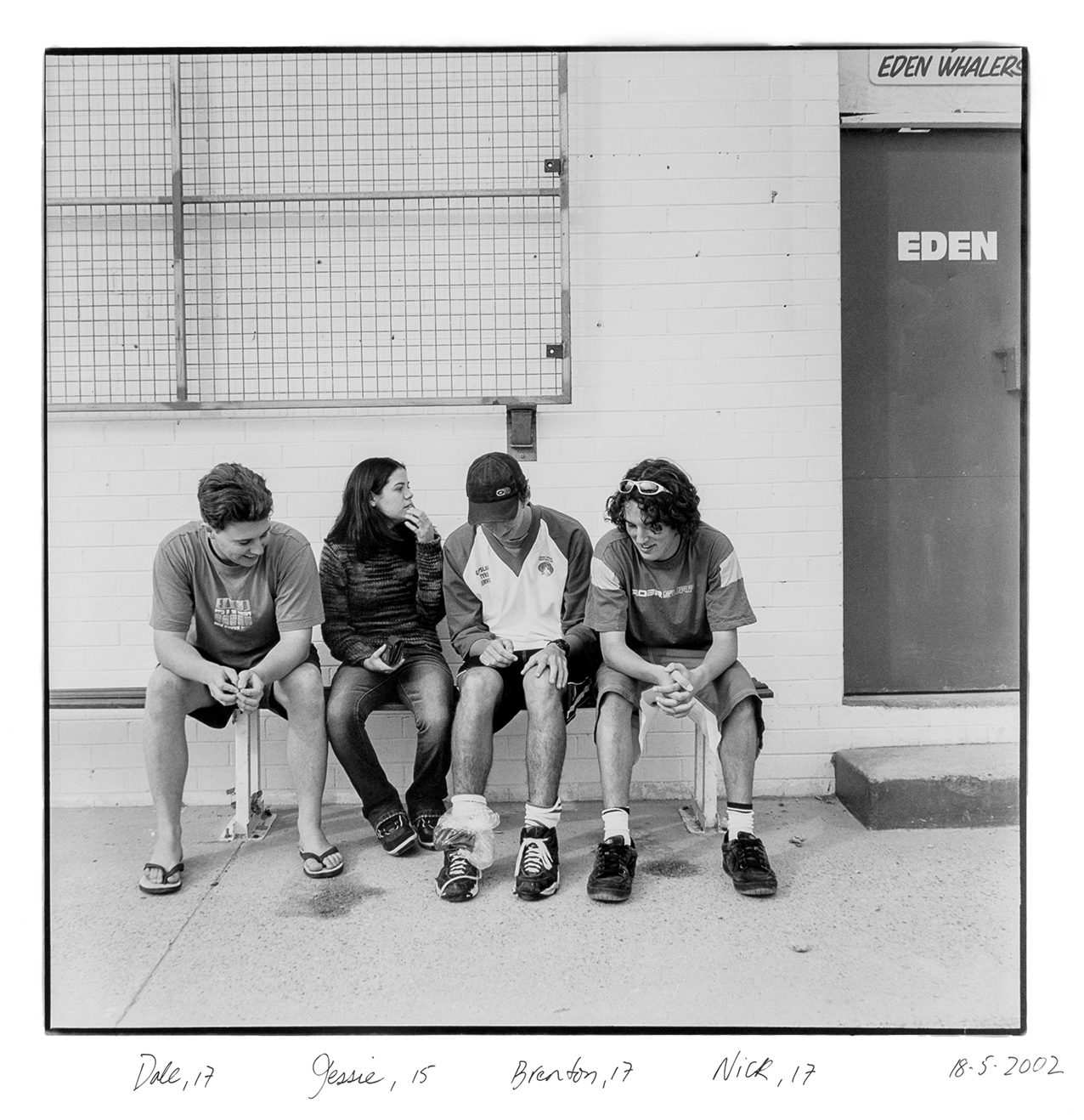

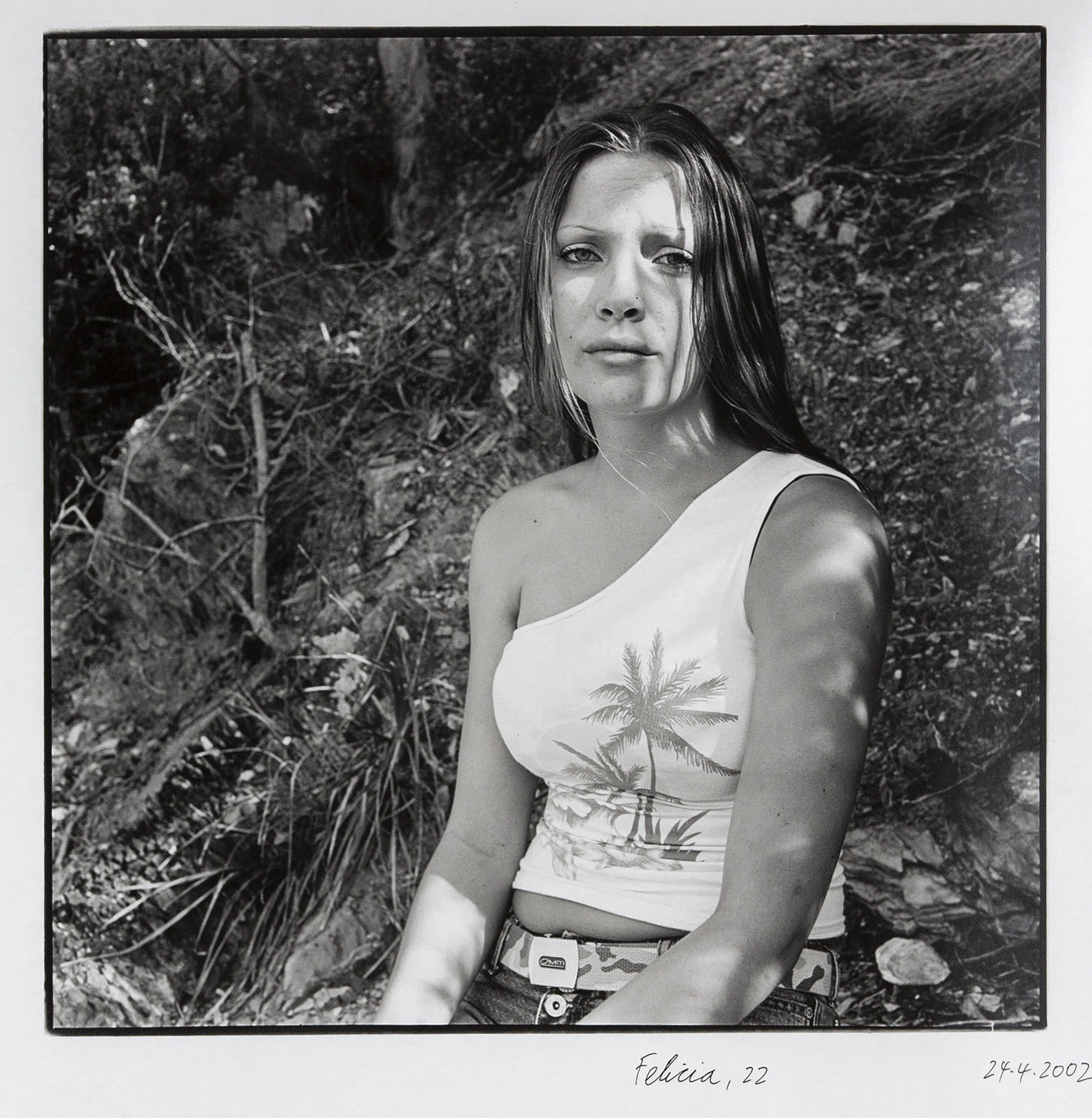

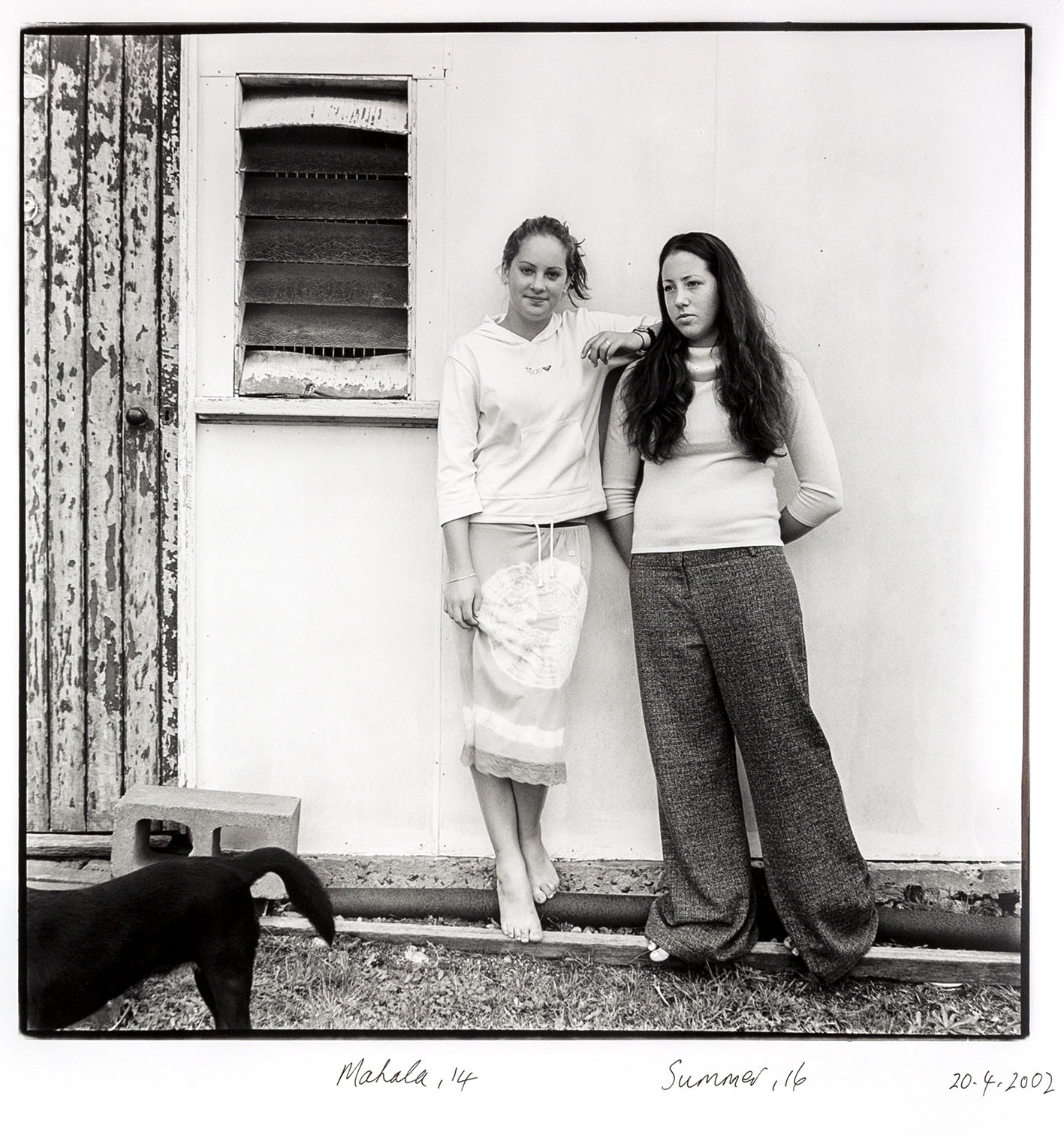

A year later I started working on a self-produced project using image & text to document local teenagers, Now a river went out of Eden, (2002). Eden is a great place for young kids, but teenagers seem to hit a wall. When I first moved here there were a lot of teenage pregnancies. There is no tertiary education in Eden and I was interested in where the teens saw their future, and what happens in a small town if the youth leave.

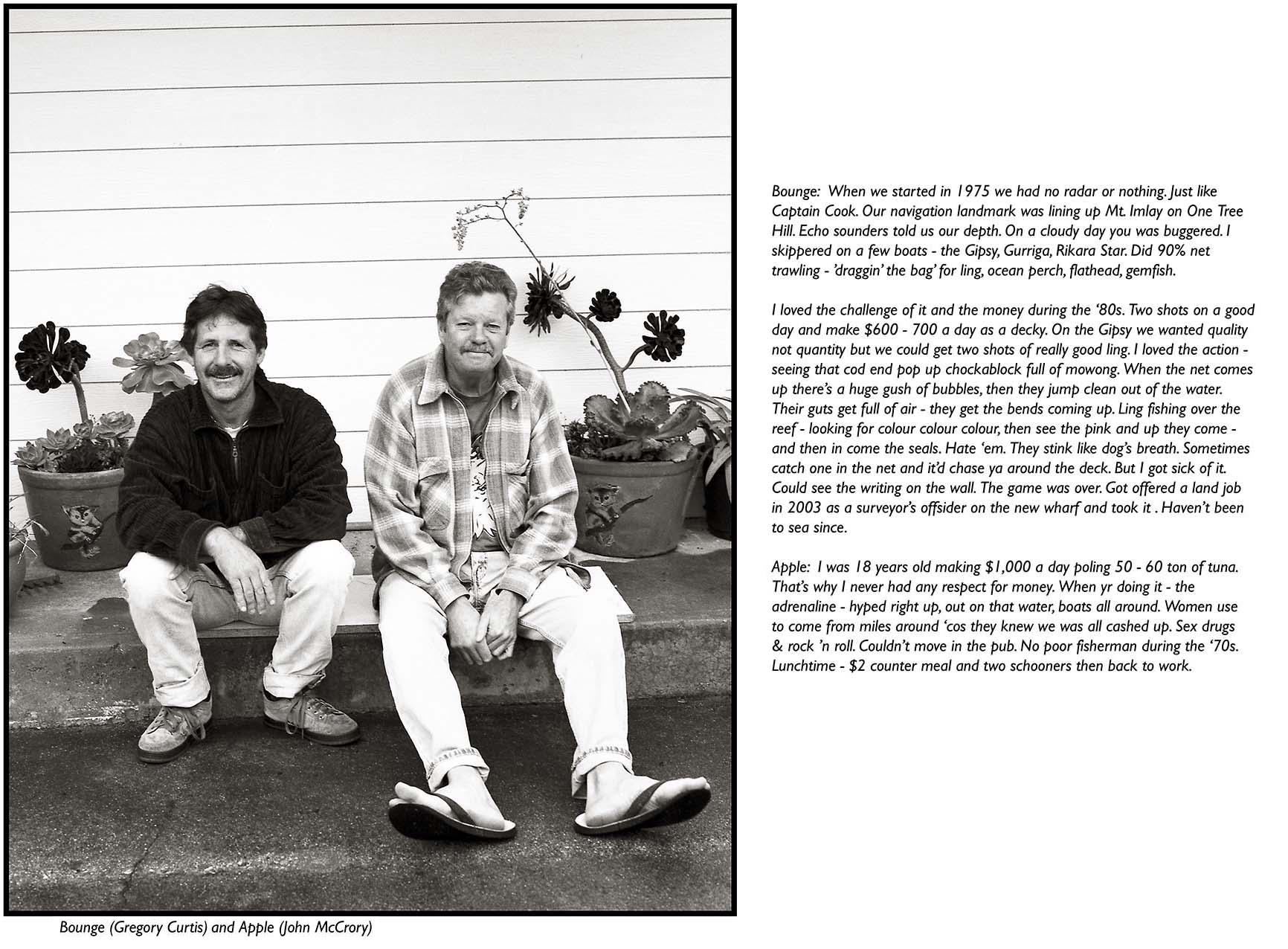

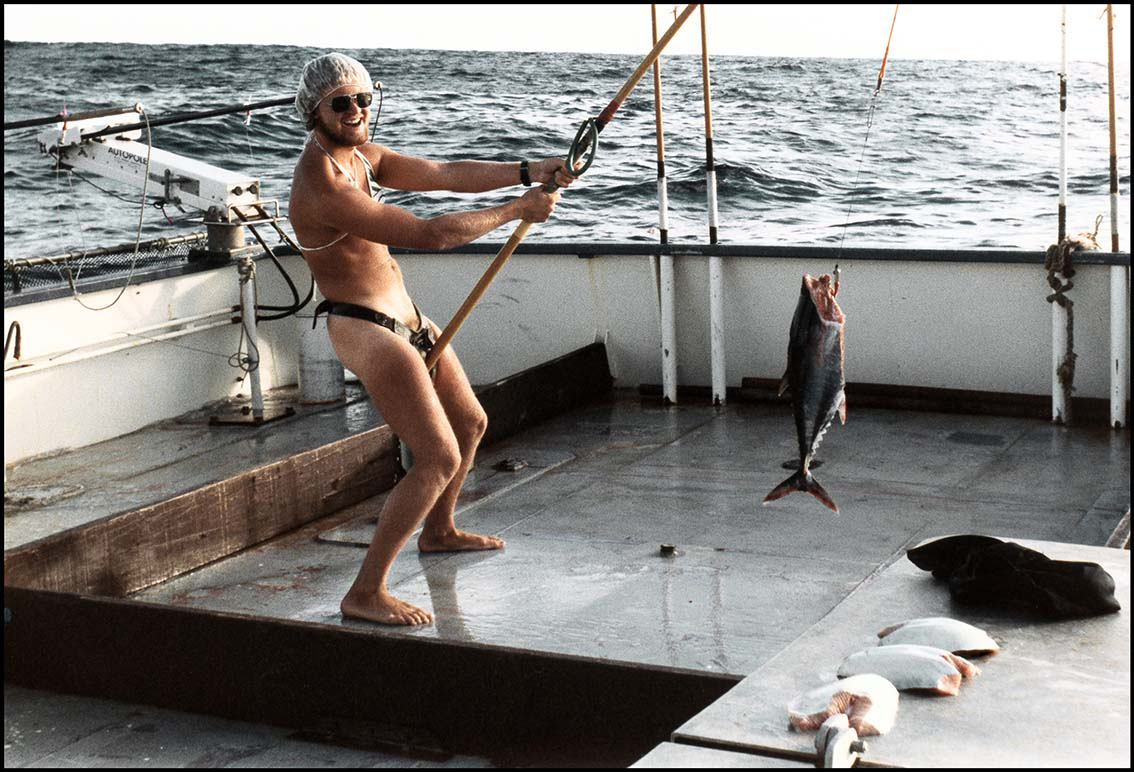

Two other separate large-scale projects using image and text are the commercial fishermen, Girt by sea (2005), and the timber workers, Can’t see the forest for the trees (2014) – two contentious industries. But employment is complex in a small town, and I think of a work site as a community of workers, and most workers take pride in doing their job well. These worksites – the mills, the boats – are often hidden away from public view.

For me, the commercial fishermen project was particularly interesting once I discovered that the fishermen had been taking their cameras out on the boats since the 1930s. They have been photographing their own work practices and their lives on the boats for decades. I had never heard of that before. I asked to see their pictures and soon they brought shoe boxes of images to show me, and (with their permission) I scanned hundreds and repurposed them for my own project.

Concurrently, I was making landscape related images. Photographing in the bush and around the ocean, making prints then cutting the prints into strips and weaving landscape grids, as well as making abstract chemigrams to represent landscape, and using algae, local grasses, and gum operculum to make lumin prints and photograms.

I’ve lived in Eden for 25 years now – more than half my career. It has been an incredibly productive time in relation to my practice. I leave several times a year. I don’t have a peer group here, or old friends that I have a history with. Or book shops or a Japanese restaurant. I would say I love being here in my house, in my studio, in this beautiful environment, and I love leaving here. Then coming back.

How did you balance your life as a photographer and mother?

I had already been pregnant, married, had three kids and divorced before I picked up a camera. I was 31 and my children were 5, 7 and 9 years-old at that time. I was living at Rathdowne street, Carlton, and there was a darkroom already there that Ponch Hawkes and Larry Meltzer had set up. The kids would come and stay with me there on weekends or after school, because at the time, they were living with their father. In 1978 Bob, two of my kids and I moved into a house in North Fitzroy together. From then on, every house we lived in had a darkroom so I could work from home. In Fitzroy, at McKean Street, there was a bungalow out the back, which we rigged out as a darkroom. A house in Woodhead street had two kitchens, so we turned one of those into a darkroom. I had a darkroom in a garage on Queens Parade, a shed in Fairfield… It was like that, going to look for the next house to rent, it had to have a space that could be turned into a darkroom.

You were witness to many important events and have documented subgroups and those living on the margins, as well as the artistic and political activist communities, and often get to know your subjects before making images. What was it like to be a photographer during this time, what did you see your role as witnessing and documenting these events?

All the people and experiences I have photographed come from the things I’m interested in. Sure, some is commissioned work, but they are also topics of ongoing interest and curiosity for me. All of my work is very much about connection with communities and like-minded people, as varied as trade unions to anti-war activism. These organisations and people mostly know and trust me as a photographer. A large part of my work also comes from demonstrations, such as anti-war, anti-nuclear or anti-Kennett, strike activity, picket lines, demonstrations for wars of national independence… I wanted to be there, it was my way to be there. My way to be among these important public voices is with a camera, especially in regard to demonstrations. I am the most relaxed in a crowd when I am there with a camera.

More generally, outside of the protest thing, I’m just interested in documenting my time and my milieu, which I take in a broad way. I’ve always been aware of the fact that we’re not the money-makers, we’re not the bankers, not the politicians, we’re just us, trying to get on with life, despite all the crap that goes on around us. We are the hidden. It’s just been the ordinary, everyday life, how we live, and how multi-faceted and how complex it can be. So, I do feel that I am part of it, and the camera also allows me to be separate. I feel like the camera has changed me socially. I was such an introvert growing up, and I still was when I first picked up a camera, but the camera has changed me. Now I can go up to anybody and start talking to them.

Did you know that while you were documenting all those amazing things that it was historically important?

Yes, I knew it was really important. My first ‘Ban the Bomb’ march was when I was 15. I grew up in a highly politicised household, where all of those things were forever being discussed. I was born in 1945, the bombs had just been dropped, they were my first nightmares as a kid. In 1956 we got our first TV, and it was constantly streaming concentration camp footage.

During the 70s, a few years before I picked up a camera, I got involved with feminism and the women’s liberation movement, and I already knew people like Sue Ford, Mickey Allen, Ponch Hawkes, Virginia Coventry, all of those important Australian women photographers. I had known collective living, the notion of breaking down the family unit – the blokes were home caring for the kids and the women worked. We wanted to change the world and we thought we could.

I think I was really lucky to have known all those women involved in arts, protest and especially photography. This really helped and provided a supportive community.

The exhibition at the CCP includes some of your stunning portraits of important Melbourne cultural figures, such as Helen Garner, Tracey Moffatt, Steven Cummings, etc. These are such charismatic figures, does one sitting standout?

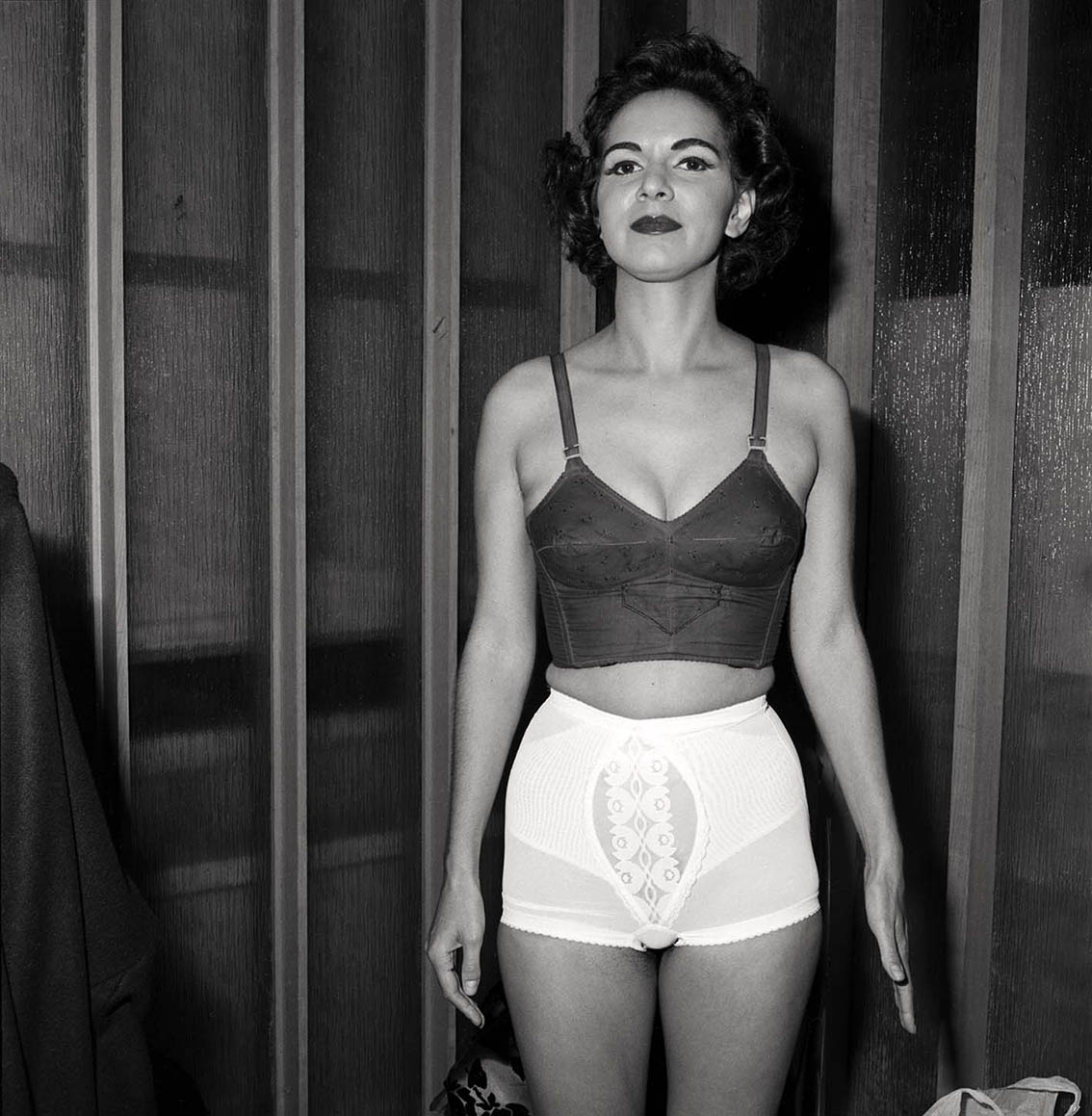

They are all such charismatic people – famous or not! I’ll tell you one story. In 1989 Tracey Moffatt made the work Something More and in the same year I was asked to teach at Charles Sturt University. I took the position but I wasn’t keen to live right in Albury, so I rented a cottage on a working farm in Thurgoona, which is about 10km out of town. Audrey Bamford, the director at Albury Regional Art Centre at that time, offered Tracey an artist-in-residency in May 1989 to come to Albury and make new work. They were talking about somewhere for Tracey to stay and I offered her a spare room in my cottage. She accepted, and we had a lot of fun. She was doing her shoots in a big shed in town and I would go in at night, sometimes with one or two of my students, and occasionally I would take a photo of the set. One night when I arrived, Tracey was preparing for a shoot. She was in her underwear and make up – she looked so good! I said to her: “Let me take a shot?” and her response was: “No. You’ll do an Arbus!” And I said, “No I’ll do a Ruth Maddison.” I took two frames, and I called the image Tracy Moffatt prepares for something more. Eventually I made a small print and sent it to her. She encouraged me to make an edition for sale. The last one in the edition of 5 is on the wall now in my exhibition at CCP.

For the CCP show you have made new work about your father, how did you begin this project and what were you interested in discovering?

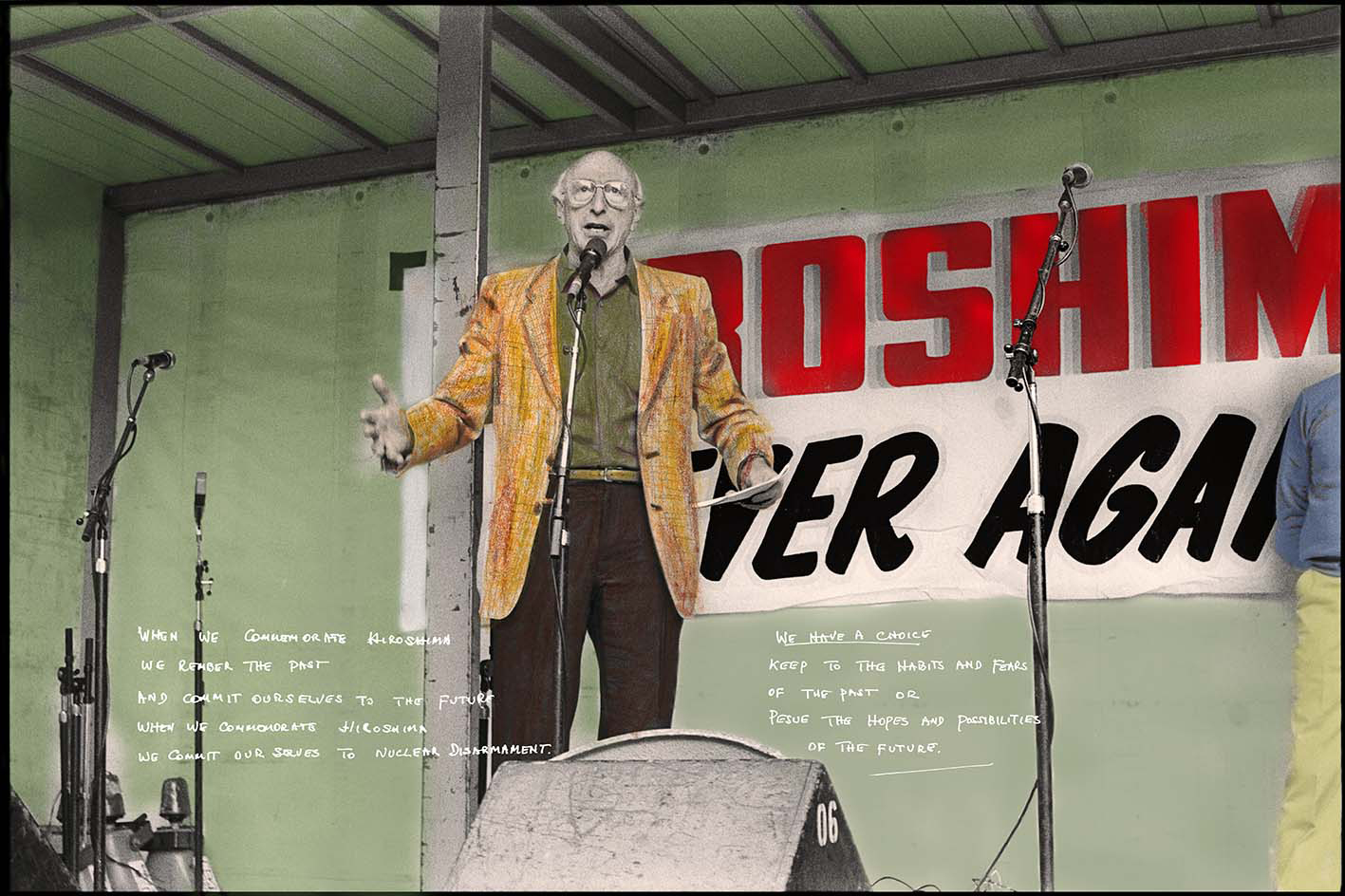

The Fellow Traveller is about the personal and political life of my father – Sam Goldbloom, who was a political activist and a member of the World Peace Council. In that capacity, he travelled to conferences all over the world. He was in East Berlin when the wall went up, he shook hands with Castro in Havana on May Day in 1981, he was in the Soviet Union in 1956 and 1963, he was in China, standing next to Zhou Enlai, with a bunch of other people from Melbourne Peace Committee, in 1956. He was in Hanoi in 1979, very early post-war. He was in Japan on Hiroshima Day several times.

My father died in 1999, then my mum died in 2008. After she died, we, the three sisters, began to clean the house out. In the garage was a whole lot of stuff that I hadn’t seen for decades, but that I remembered. When my father travelled overseas mostly to various international peace conferences, he had a movie camera and he made movies and when he got home we would watch them. They were all there, as well as boxes of slides, his written notes preparing for speeches, etc. So, I said to my sisters: “I’m taking these, I’m the visual one.”

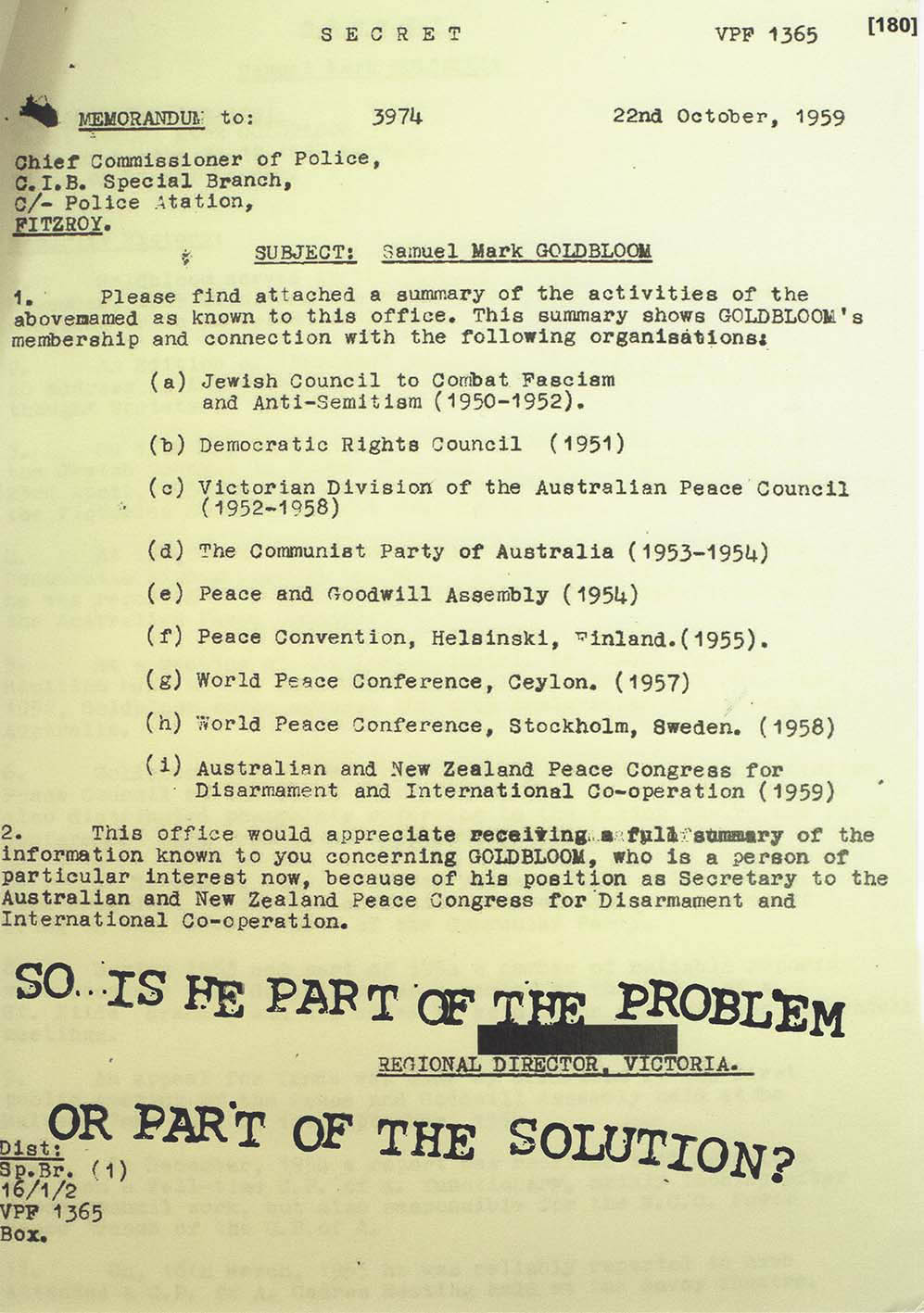

It wasn’t until a couple of years later I decided to get the movie footage digitised and I started sifting through the material. I then found out about two archives on his political life. One at Melbourne University Archives, and his ASIO files at the National Archives of Australia. I started researching and photographing at both archives and eventually thought: “Maybe I can make something with all this stuff.” That’s how it really started.

History is always a version of history. History is written by the winners. History is always mutable when new information comes to light. So, I thought, maybe I can make a version of history, that’s part real, part memory, part imagination. I think about it as a stream of consciousness as I come to material or as I think of him. Real and imagined things come to mind when I think about what I can make this look like.

As children we knew about his political life, and we knew the family was being watched by ASIO. When we were kids in the 1950s, I remember mum and dad saying: “Those people are going to sit out in that car, all day and all night, don’t worry they’re not going to say anything to you, they won’t do anything to you, they’re just watching everything – and every time you pick up the phone you will hear a click, but don’t worry about it…”.

Sam was in the newspaper, he was vilified in parliament, then ended up being awarded an Order of Australia Medal for peace activities in 1990. It’s interesting, that cycle of how history shifts and changes. Now there’s a street named after him in Canberra, Goldbloom Street, in an area where streets are named after social activists, in the same town where I’m researching all these fucking ASIO papers.

Did your father’s radical political activities have an effect on you?

Yes, sometimes it did, I remember when I would get on the tram to go to high school, and someone would yell out: “How’s your father’s communist peace movement going, Ruth?” It was terrible, because I was so introverted. Sometimes I would say to dad, to Sam: “Why can’t you just be an ordinary father?”

My father’s activity also brought the anti-Semites out of the woodwork as well. Some really shitty things happened. I remember one day, I went outside and got the newspaper and overnight someone had painted with white paint in large letters on our outside wall: “Get out Jews!” It was really freaky. Freaky to think that that goes on in the night when you’re asleep. Dad would get anti-Semitic notes in the letter box that said things like: we’re going to come and get you and your family. So that stuff was very disturbing, but it passed because nothing actually happened and my parents handled it very well.

The truth of it is, my parents gave me a very colourful life, a really rich life. All the discussions around our table, all these incredible people who were coming here for peace conferences, were at our table. It was just a really vital, energetic and interesting way for me to grow up.

Finally, do you have any advice for aspiring photographers?

Who listens to advice? If people ask me stuff, I talk about my experiences.

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better”. (Samuel Beckett) or “Make your own mistakes.” (Alan Rickman). Make more images, keep making images that take you on that journey, it’s all about that process…