to set fire to the sea was made in response to the Australian government’s policy of mandatory, indefinite immigration detention. This system of bureaucratic violence is driven by the Australian government’s moral panic around refugees and fixation with border control within a global climate of mass displacement and nationalism. The Australian immigration detention regime has operated in variations for over twenty years, forming a part of this country’s complicated history of colonialism, migration, identity and belonging.

This project is a collection of fragments from stories of the ongoing life and conversations with friends who are currently in detention centres, have been “released” into community detention, or granted temporary asylum in Australia. This project attempts to speak to the interiority of living in indefinite detention, and how existence in this liminal space is rendered largely invisible and often reduced to spectacle.

Signage for Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre removed and painted over while the centre was in operation.

Asylum seekers who arrived by boat were given a unique number for identification purposes. Detention centre staff have been known to call asylum seekers by their boat number instead of their actual names.

Moorthy was recognised as a refugee in 2011 but never received a visa. His nickname in detention was “more tea” because he would make everyone tea during visits. We calculated that he would have made approximately 21,840 cups of tea in his time in detention.

“This is how tired we are, this action will prove how exhausted we are. I cannot take it anymore.”

Omid Masoumali, a 23 year old man from Iran, had been living on Nauru for three years. On 26 April 2016, during a visit from UN Officials, he set himself on fire.

When I first started visiting Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation (MITA), the visiting room was always lively and full of people. People would write their names and contact details on scraps of paper for you to visit them again and keep in touch in the meantime.

Eid Moon. Visits were especially quiet during Ramadan. When I asked why it was so quiet, I was told people were too tired and too sad to come to visits.

Ismail said he used to have beautiful hair. He said after four years in detention his appearance has completely changed. Stress diminished his appetite, and he was being given medication to sustain his energy. He said he would eat two slices of toast a day.

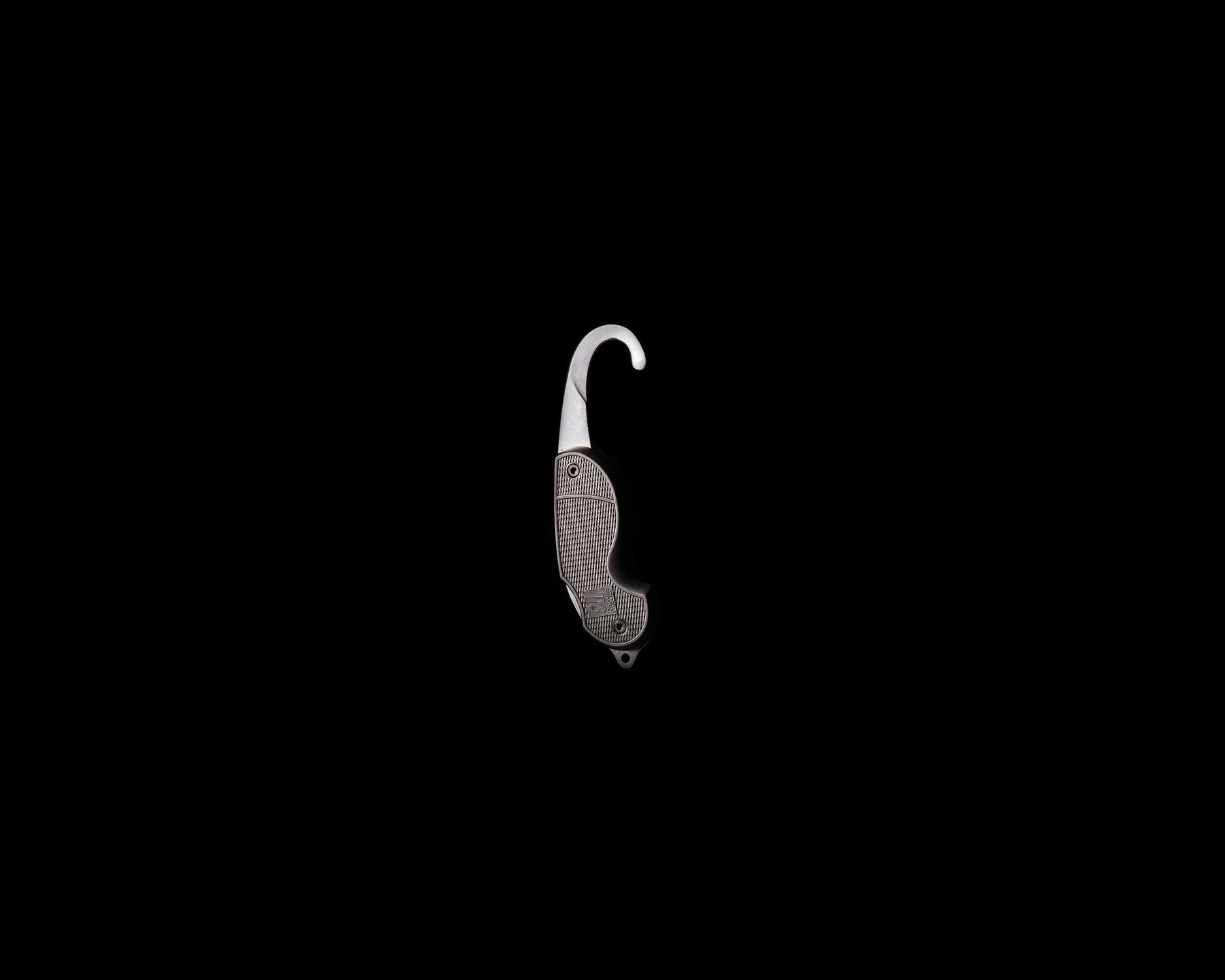

Guards in some detention centres are required to have a Hoffman knife. These are used to cut down detainees found hanging.

Ismail talked about funny times in his shared room; heavy roommates on wobbly bunkbeds, loud snorers and bumping his head on the ceiling when he woke up. But also other times, when his roommate would wake him up because he was crying in his sleep.

Paari spent the first years of his life inside Villawood Detention Centre. For his third birthday, he wanted a key.

In Rujul’s old bedroom.

In August 2017, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection introduced the ‘Final Departure Bridging Visa E’ affecting asylum seekers in community detention. Within three weeks of the announcement welfare support ceased and people were evicted from community housing. They were required to find a job, a place to live, and make arrangements to return to offshore camps or to their home country within six months. This temporary visa has been reissued every six months, leaving individuals in recurring limbo.

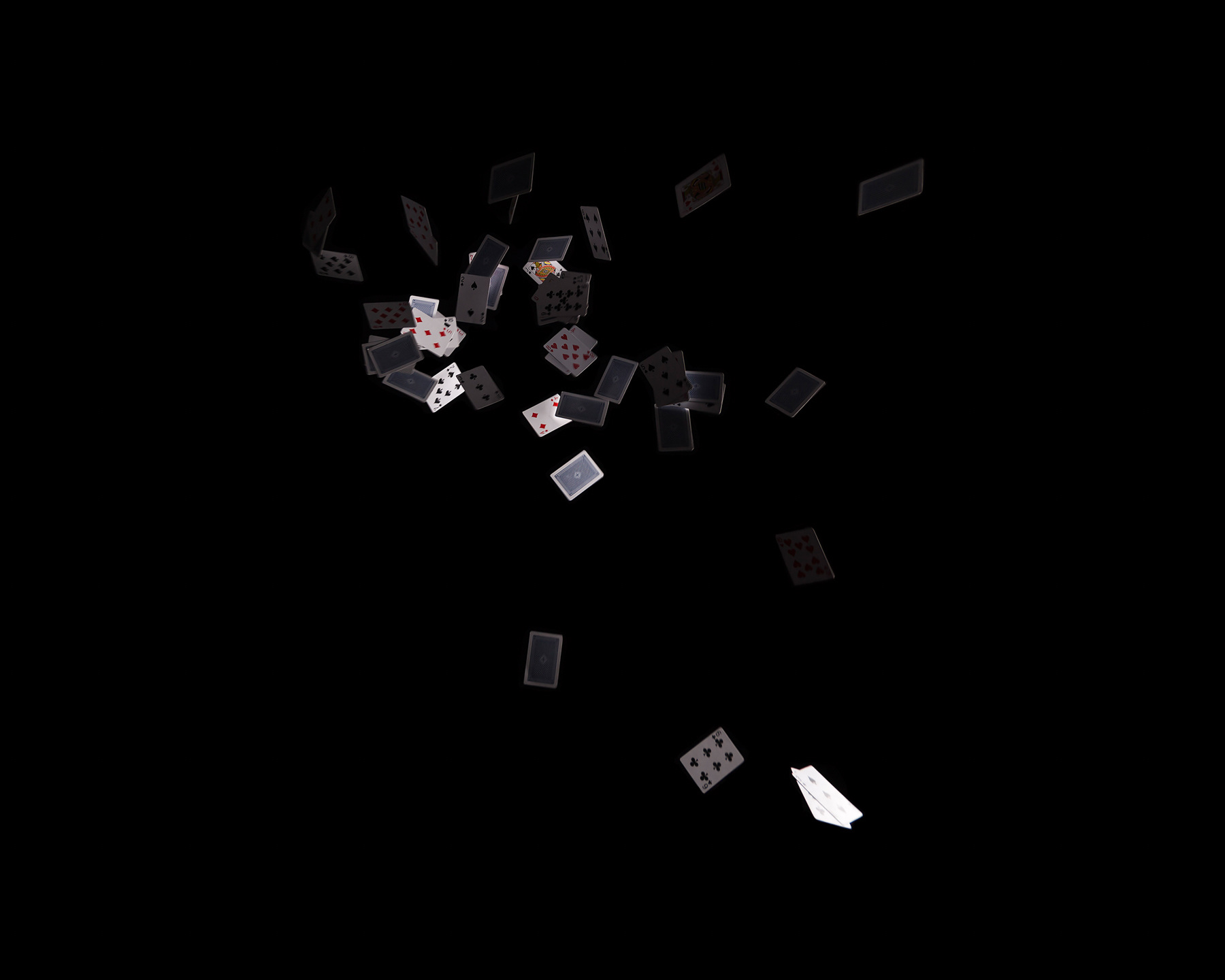

Nima and I are the same age. He has four qualifications and likes to play the violin. The first time we met, he had our whole table captivated with his card tricks. He was detained for five years. The processing of his application for asylum began in the fourth year.

A counsellor in a Perth detention centre would tell detainees to blow up a balloon and when it burst, he would say to them, ‘this is life’.