My visually based project titled Telia involved the production of a photobook consisting of archival artefacts (including documents and photography) and self authored photography. The broader project for exhibit also includes a series of video poems.

Together the photobook, and video poems attempt to reanimate and reexamine the experiences of the men who came from undivided India and worked as hawkers or travelling salesman within rural Australia. The men worked both prior to and immediately proceeding the introduction of the 1901 Immigration act or ‘White Australia Policy’ as it was more commonly known.

At a macro level Telia is a research based project incorporating photography and video that explores the role of the visual in the construction of history. At an applied level the work seeks to contribute to the study of South Asian presence in Australia and to contextualise this within Australian racial hegemony, both past and present.

While my photographic and collected archivally based materials engage directly with narratives and histories that are somewhat external to my own, my video work attempts to contextualise and link my own presence and experiences to the photographic and archival based artefacts that I recover, create and animate.

The disparate, existing visually based history of the men who worked as hawkers is re-contextualised within Telia through the construction of new visually based artefacts in order to create contemporary and dynamic narratives and interpretations of histories.

My practice within Telia, involves the utilisation of both archival material and the creation of self-authored photographs. In this sense my work aligns with the methodology stated by Fontcuberta that, “preserving a sustainable equilibrium within the universe of images requires coordinating the containment of production with acts of recovery.” Put more simply Telia is an attempt to rationalise new image production with that of utilising existing visually based material to develop my expanded narrative. I utilise this methodology in recognition of, and as a counterpoint to, the photograph being ubiquitous in daily life.

While both photography and history are structurally subjective in nature, Telia is an attempt to create an authoritative research based work that incorporates historical experience and visual artefacts, while also acknowledging numerous relevant constraints of working within the medium of photography and the construct of history.

That photography broadly exists within a populist misconception of being the ultimate medium of ‘truth’ has prompted me to create a broader and more subjective narrative that may lead audiences to engage in a deeper thinking upon some of the issues of sociopolitical importance within regard to an Australia, both past and present.

As an Anglo-Indian my own life experience within both the wider Australian and Indian societies and through the associated cultural bodies of each social group was invaluable in assisting me to attempt to understand the experience of cultural dislocation that the men who worked as hawkers may have faced.

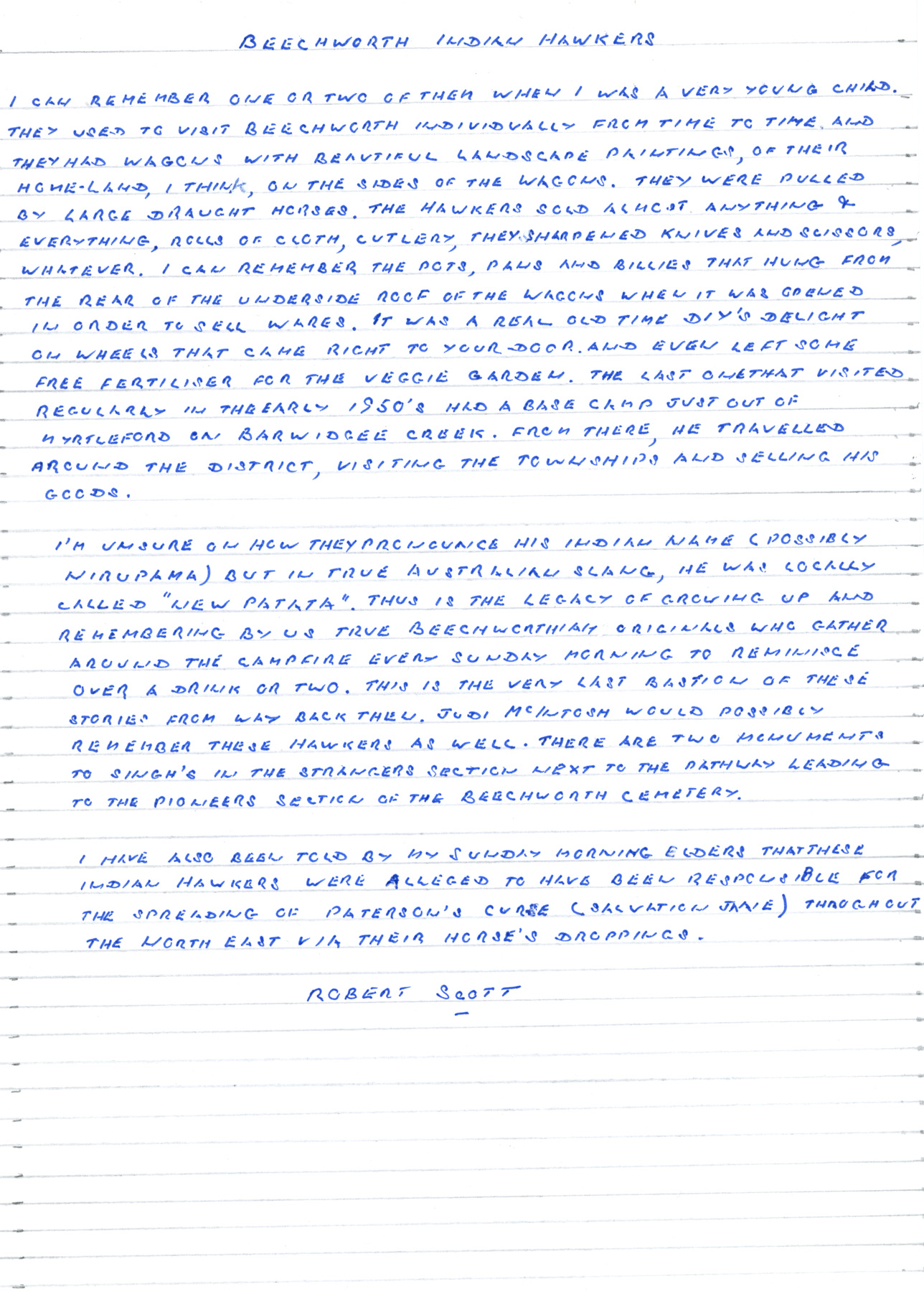

Petition, early 20th Century

A petition from the Avon Shire Council to the Victorian Parliament in Australia seeking a decentralisation of the licensing process for hawkers as a means to combat a perceived ‘Indian hawker nuisance’.

Harmel Uppal, Wolverhampton, UK, 2019

Harmel’s Great uncle Pooran Singh was an Indian from Punjab who migrated to Australia as a 30-year-old man in 1899 to earn money for his extended family in India. Pooran worked as a hawker in the state of Victoria and died 48 years later in 1947. Throughout his working life in Australia he repatriated money to his family in Punjab and upon his death he left 1500 pounds in equal shares to his four nephews as he was never married and had no children of his own. The family used the money to build a house and placed a plaque upon the house bearing Pooran Singh’s name. In 2010 Harmel Uppal traveled to Australia to repatriate his great uncles Ashes to India after he discovered that they had remained uncollected since his death in Australia 63 years earlier.

Abdool Qadoos, Khaliq Dad and Mahroof Hussain Rashid, Rotherham, UK 2019

All had forefathers who worked in Australia as hawkers. In 2019 the three men were in the midst of converting a disused church in Rotherham, where they live in the UK, into a mosque. They envision it as being a place for the broader community to gather, regardless of faith.

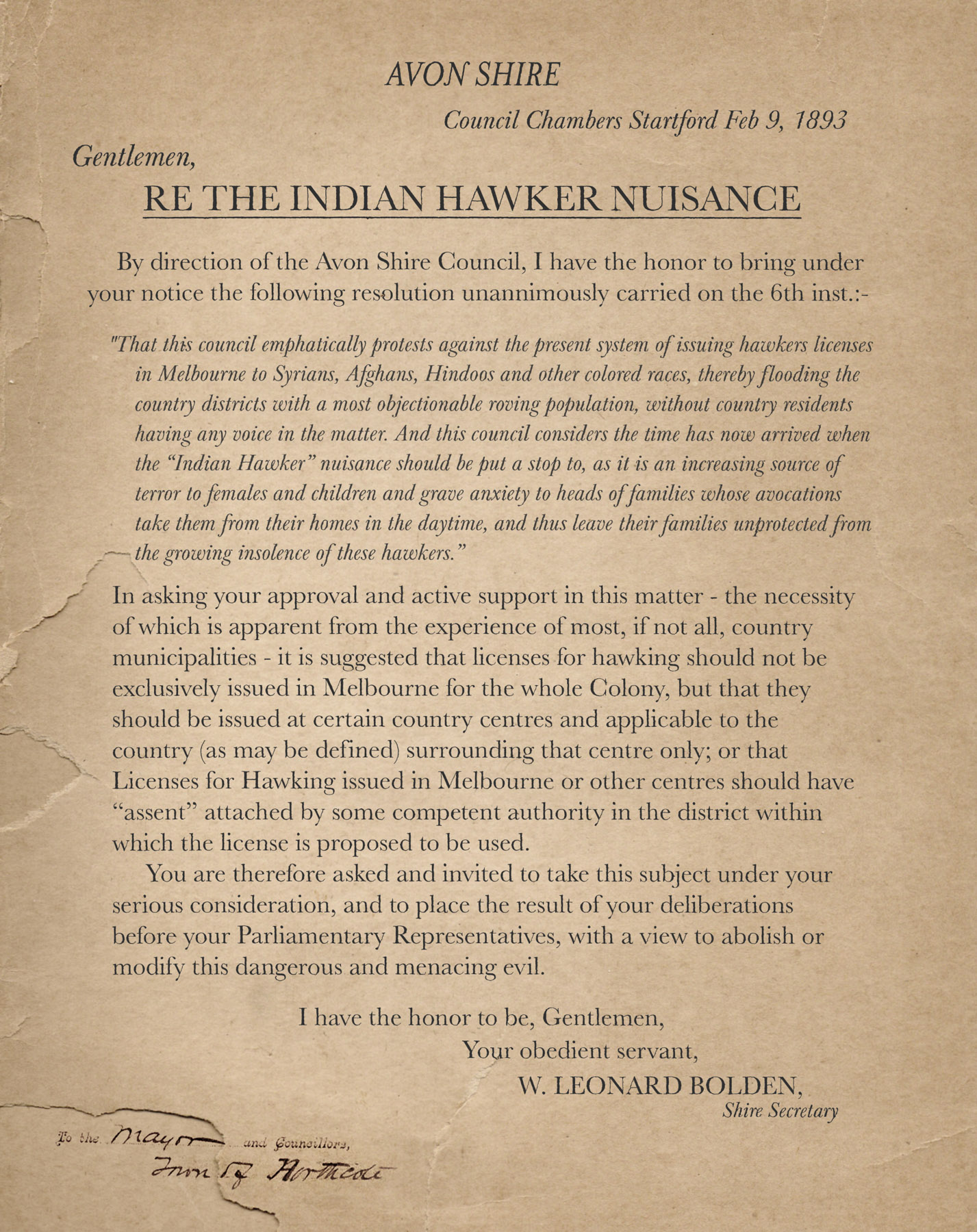

Handwritten excerpt from Khawaja Bux’s diary outlining his beginnings hawking in Australia in the early 20th century.

Haroon Bux, Auburn Mosque, Sydney, Australia, 2020

Haroon Bux is the great grandson of Khawaja Bux. The Auburn mosque in Sydney’s west is a significant place for him. His great grandfather also helped raise funds for the building of the first mosque in Perth.

Sucha Sihota Singh, Jalandhar, Punjab, India 2020

Sucha Singh Sihota is the grandson of Hukam Singh who worked as a hawker in Leitchville, New South Wales. Hukam Singh periodically repatriated money to India that he earned from hawking in Australia. Using this money Singh’s family built a house in his native village of Barapind in Punjab. His great grandson and great grand daughter in law still live in the house and have his portrait hanging above their bed. The same image also hangs on the wall of Sucha Singh Sihota’s house in Jalandhar on the top right of the wall behind him.

Jalandhar, Punjab, India 2020

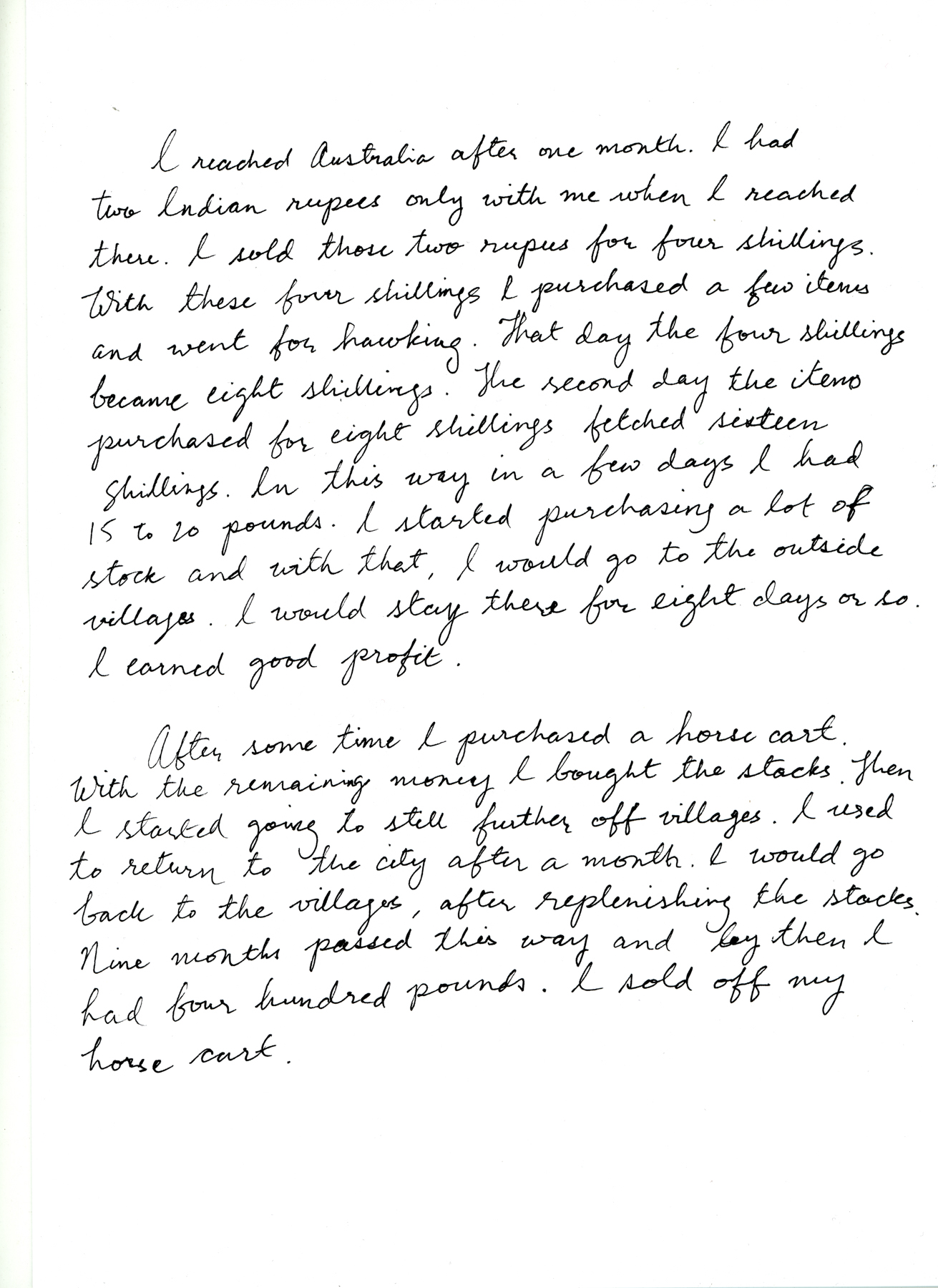

Passport photo’s from Australian government documents for Monga Khan

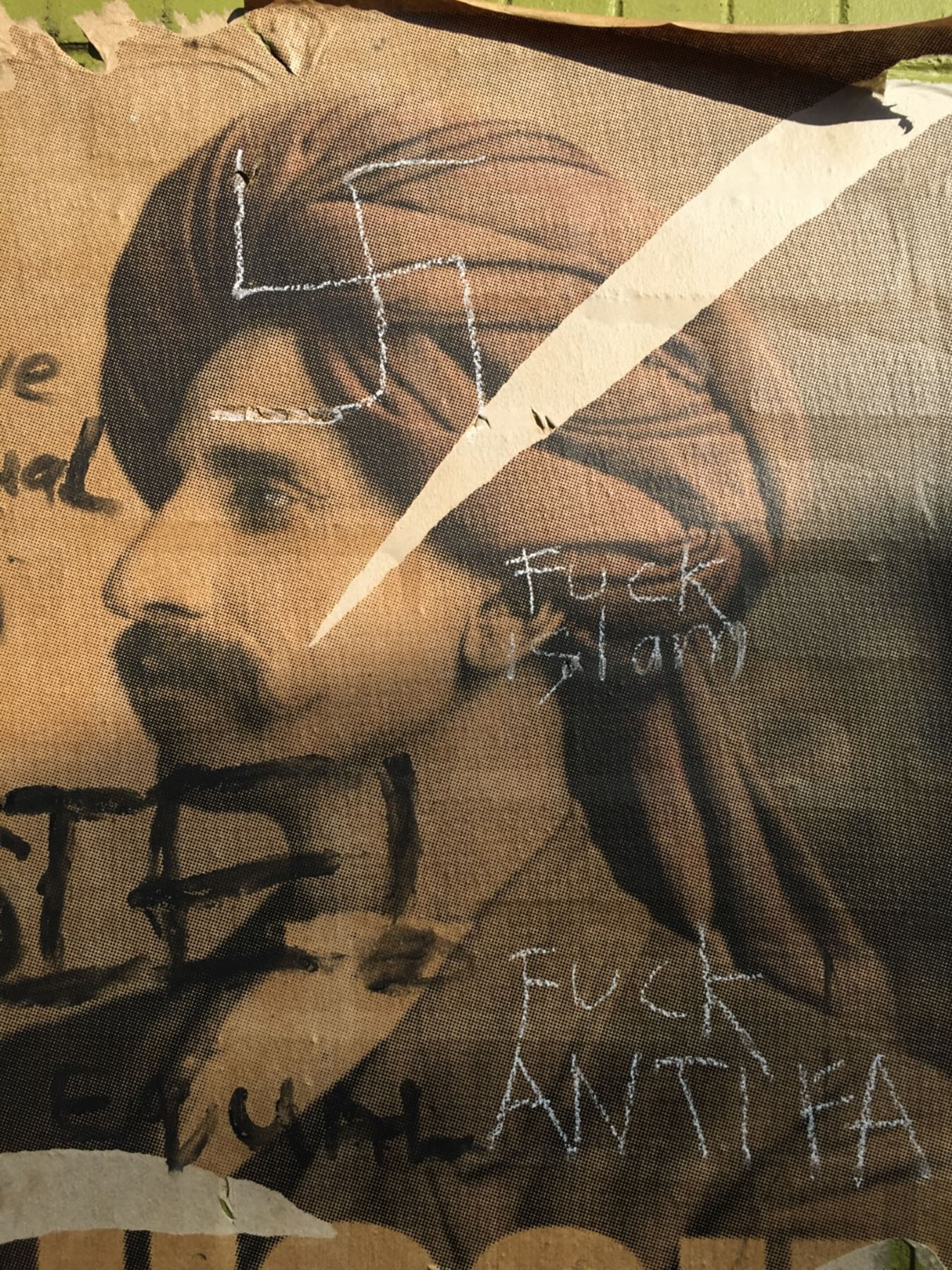

Monga Khan migrated from Punjab and worked as a hawker throughout the Ballarat district of Victoria in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 2016 he became the unwitting face of a crowd funded anti-racism art project. His likeness, as imagined in the artist’s work, was defaced with racial slurs at Sydney’s Green Park station almost 100 years after his death.

Four generations of descendants of Monga Khan, Birmingham, UK, 2019

Defaced anti-racism poster featuring Monga Khan, Green Park Station, Sydney, Australia, 2019

Beechworth Cemetery Victoria, Australia 2019

A sign at the Beechworth cemetery in North West Victoria. Within the strangers section stand two headstones of men from India who worked as hawkers in the local area. It was common for hawkers from India to be interred away from other graves and to be buried rather than cremated even if their religion specified cremation.

Ali Buc (right and unknown compatriot) Victoria, Australia c.1935

Ali Buc migrated from Punjab and worked as a hawker around the area near the Grampians in country Victoria. He is buried in the Dunkeld cemetery, upon its very edge, 63 metres away from the nearest grave.

Dunkheld, Victoria, Australia 2019

Ali Buc’s grave. Dunkheld cemetery, Victoria, Australia, 2020

The words ‘Indian Hawker’ are inscribed upon his tombstone.

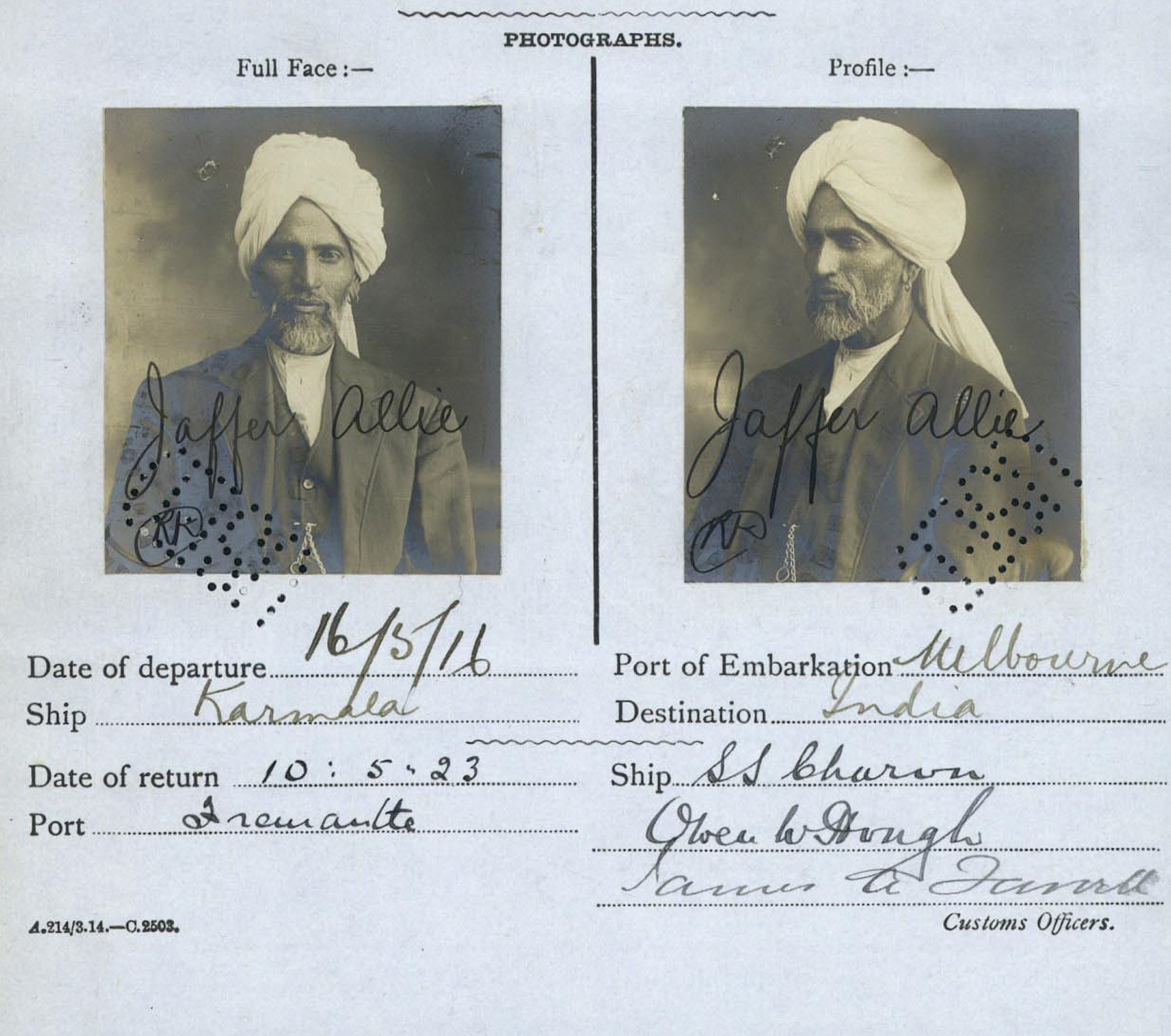

Australian government document issued to Jaffer Allie in 1916

Jaffer Allie was a hawker, so that he could re-enter Australia on return from visiting India. The certificate meant that the holder did not have to sit a 50 word dictation test in a language of the custom’s officers choice as was common for non Europeans under the White Australia Policy.

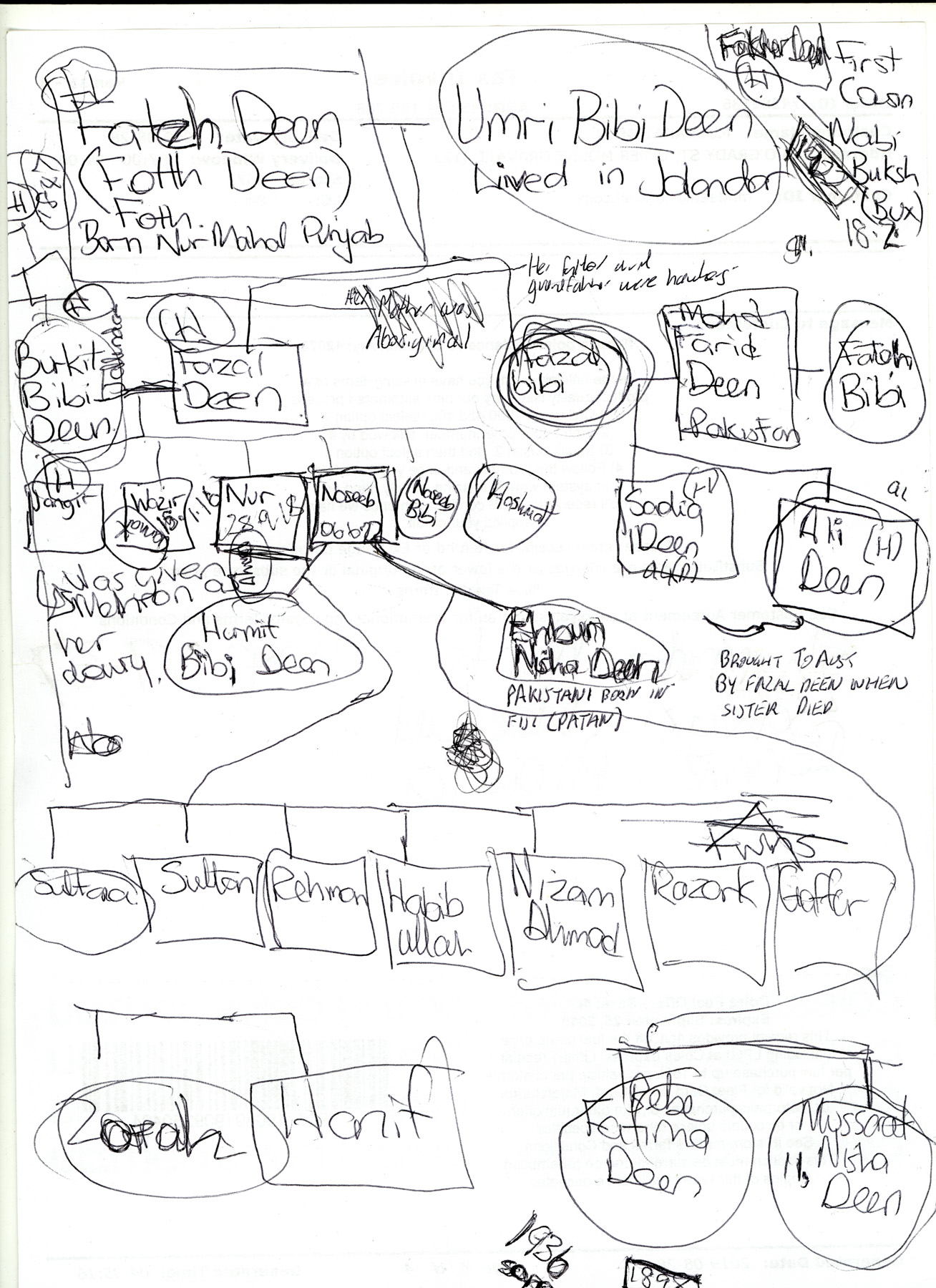

Family tree drawn by Mussarat Nisha Deen, great grand daughter of Fotth Deen (drawn in 2019)

Fotth Deen began his life in Australia as a hawker after migrating from undivided India as a young man in 1890.

Fazal Deen and unknown compatriot with Fazal’s Chevrolet truck bearing his father’s name, Brisbane, Australia, circa 1930

Both Fazal and his father Fotth used this truck for hawking goods in rural Queensland. The truck was purchased by Fotth Deen in 1916 and was chain driven. It allowed him to vastly expand both his hawking and other business activities.

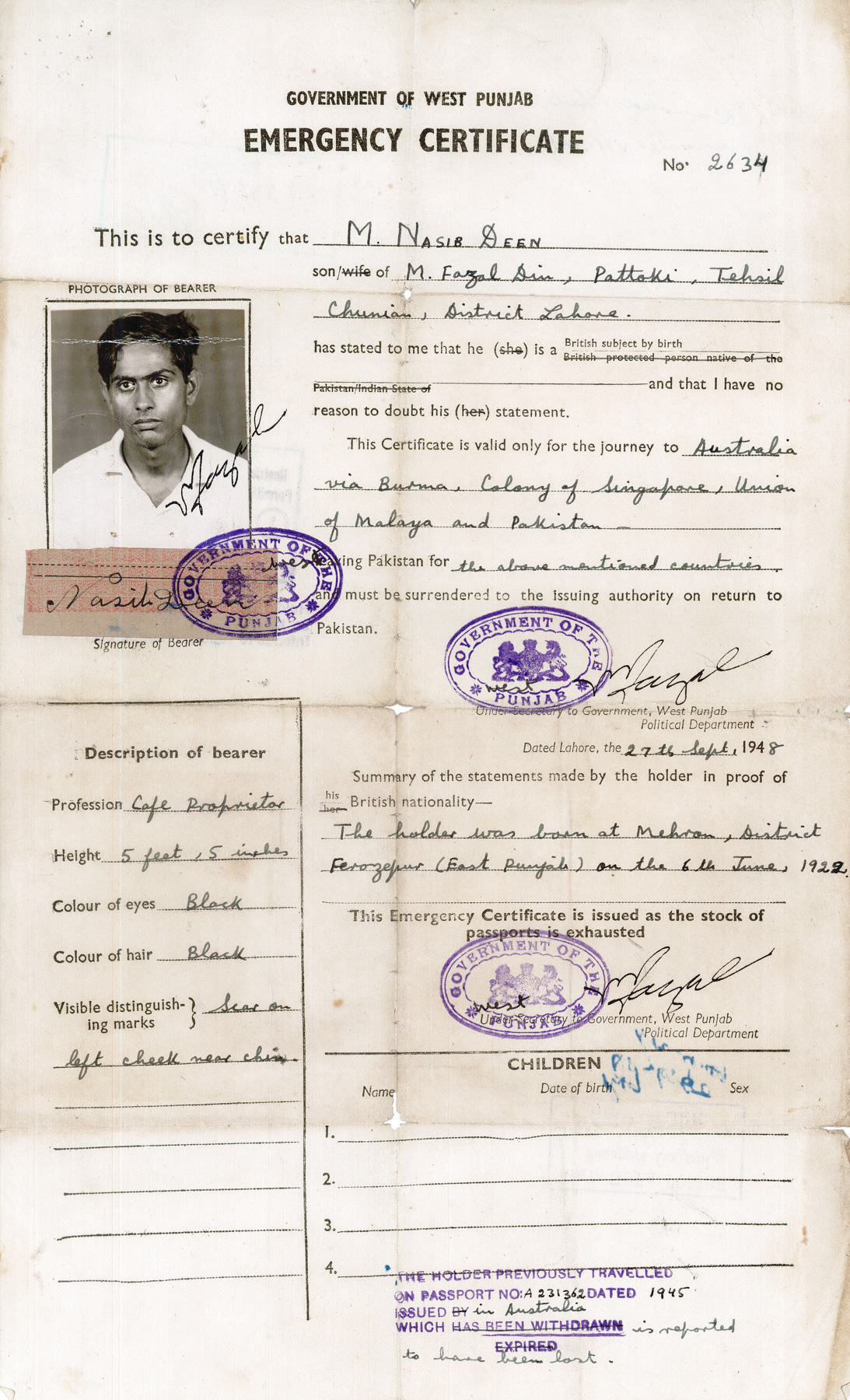

Fazal Deen’s son Nasib’s emergency certificate issued in 1947 and allowing him to leave India and return to Australia at the time of the partition of India

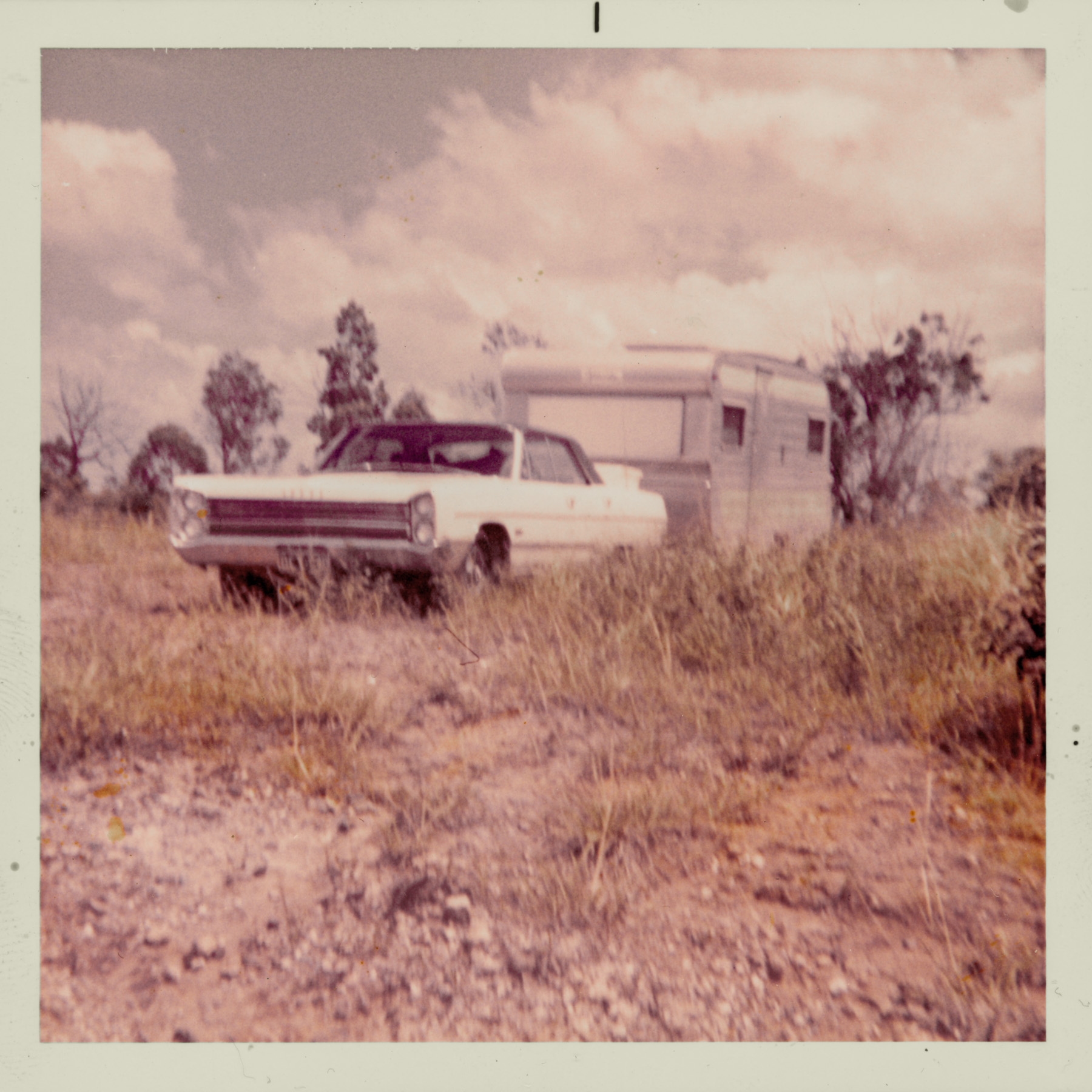

A Dodge car and a caravan used by Nasib Deen when he returned to hawking during the period 1961-64

Nasib Deen sold cushions specially designed for the rear parcel shelves of cars. They were made in the family home by his children. Nasib’s children worked for three hours each day after school hand making the cushions that were often embroided with the names of different makes of cars. His main customers were petrol stations and he sold to them primarily upon a commission basis. Nasib Deen traveled an arduous route for months at a time selling the cushions, from the North Coast of New South Wales to Cairns in Far North Australia. He initiated this business when his other enterprises came under pressure.

4th grade photo including Fotth Deen’s great grandson Hanif Deen

Item sold by unknown hawker in Victoria, Australia, early 20th century